- Home

- Ann M. Martin

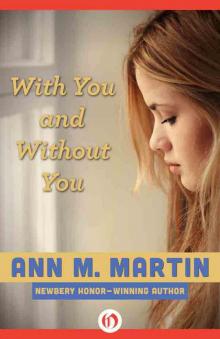

With You and Without You

With You and Without You Read online

With You and Without You

Ann M. Martin

This book is for

CLAUDIA WERNER,

for all the years.

Contents

BOOK I Autumn

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

BOOK II Spring

Chapter One

Chapter Two

BOOK III Autumn Again

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

EPILOGUE

A Personal History by Ann M. Martin

BOOK I

Autumn

Chapter One

NOVEMBER 12 WAS NOT the greatest day in my life. I plodded home from school that afternoon thinking about a piece of bad news I’d received: my English teacher had announced that our class was going to participate in a winter pageant before Christmas vacation. I wasn’t sure what a winter pageant would involve, but I didn’t like the sound of it. I would probably have to do something on a stage before an audience, and that was worrying me.

I was also worried about my father. He’d been very tired lately, and ever since last summer he’d been getting short of breath. Sometimes his legs would swell up. So he was going to visit our family doctor that afternoon. It was his second visit in a week. But since Dad was usually as healthy as a horse, the idea of having to be a snowflake or a surgarplum was more on my mind.

The day was bitterly cold. We were in for a hard winter according to The Farmer’s Almanac, and also according to my four-year-old sister, Hope, who had spent a lot of time studying the stripes on the woolly bears. The stripes were very wide, and Hope’s daycare center teachers said the wider the stripe, the harder the winter.

I pulled my scarf tighter, lowered my head against the wind, and quickened my pace. The sky was steely gray, that harsh, sharp sort of gray you find sometimes in the eyes of German shepherds. It was a color I disliked.

I turned the corner onto Bayberry and hurried by the Hansons’ house on the corner with its untidy yard and the dogs whining in their pen. Then I hurried by the Whites’ immaculate house and waved to Susie and Mandy, Hope’s friends, who were trying to jump rope, but who were so bundled up they could hardly move. The Petersens’ home was next (my best friend, Denise, lived there), then came the Washburns’, and across from their house was 25 Bayberry Street. I always approached our house from the other side of the road so I could get the fullest view of it. I stood in front of the Washburns’ for a few seconds, just looking.

Our house was very special to me. It was the biggest and oldest house on Bayberry Street, and generations of us O’Haras had lived in it. It had been in our family ever since it was built, almost two hundred years ago. The house grinned a welcome to me. I noticed that someone, probably Mom, had hung a bunch of dried corn on the front door that morning—a sure sign of Thanksgiving and the holiday season. The corn would stay up until it was time for the Christmas wreath. I smiled, feeling momentarily satisfied and excited, and took off across the street in a run.

I ran all the way up the lawn to the porch and leaped up the four steps in two bounds. Then I slipped the house key from around my neck and let myself in.

“Hello?” I called, slamming the door behind me.

No answer. I was the first one home. Some days I liked the peace and quiet, some days I didn’t. That day, feeling uneasy about the pageant, I longed for a little company, my sister Carrie’s in particular.

I was what my mother and father called a latchkey kid. Brent, my brother, and Carrie were latchkey kids, too. Our parents both worked, and we three older kids were on our own from three o’clock, when school let out, until six or so when our parents came home. Hope was not a latchkey kid. She was too little, and Mom and Dad didn’t want her to be a burden on her sisters or brother. That was how she wound up in day care.

Every weekday morning at seven forty-five sharp, Mom or Dad or sometimes Brent, now that he could drive, would drop Hopie off at the Harper Early Childhood Center, a fancy day-care operation where Hope remained under the watchful eyes of Mrs. Annette Harper and three capable teachers until someone picked her up in the evening.

All us O’Haras called the HECC “Hope’s school,” and Hopie felt very proud that she went to school all day just like Brent and Carrie and I did. None of the other little kids on Bayberry Street could claim that.

There were two reasons why both of my parents worked. One, they enjoyed it, and two, we needed the money. Not that we were struggling or anything. In fact, we had plenty of money. But believe me, we needed plenty of money for the upkeep of our big, old house and its three and a half acres. In a house as old as ours, something was always breaking or on the verge of breaking, usually in one of three areas—the basement, the kitchen, or a bathroom. Then, too, Mom and Dad were facing four college educations, and Brent’s would start in less than two years.

So Mom and Dad worked. My mother was the head of the English department at the Covington Public School System. We lived in Neuport, Connecticut, and Covington was the next town over. Mom had decided years ago that she would be wise to head up the English department of a school system her children were not a part of.

My father was an account executive at a hotshot advertising firm in New York City. He commuted there on the train every day. Dad handled accounts like Calvin Klein jeans and Chanel perfume. When I was little, before I developed stage fright, I used to beg him to put me in the commercials for his products. Now I understand that he didn’t have any control over that sort of thing.

I hung up my ski jacket, put away my scarf and mittens, set my school books on the dining room table, and got two brownies out of the cake tin.

I opened the refrigerator and stood in front of it, looking at all the pots and plastic containers and mysterious foil-wrapped packages, and tried to figure out what to fix for dinner. Brent and Carrie and I were in charge of dinner on weekdays since we got home earlier than Mom or Dad. I decided on broccoli, potatoes in their jackets (a favorite of Hopie’s), and baked chicken legs. I closed the refrigerator. Everything could be started later.

I was about to crack my math book when I heard a scratching at the back door. It was Fifi, begging to come in. I could hear her whining as I unlatched the door.

“Feef!” I cried as she bounded in, bringing a gust of frosty air with her. “You must be freezing.”

“Woof!” she agreed happily, standing on her hind legs to kiss my face.

Despite her name, Fifi is not little and is not a poodle. She’s a gorgeous golden retriever. Brent got her for his birthday six years ago. At the time, he thought naming her Fifi was hysterical. Now it’s just embarrassing, but there’s no changing a dog’s name. Fifi would never answer to anything but Fifi.

Fifi trotted after me as I headed for the cabinet where her kibbles and chow and the cat food were stored. She looked happy and smug, probably thinking, I knew she’d give in.

I gave her a biscuit shaped like a mailman, and she took it delicately between her teeth and, without being told, settled down in the kitchen to eat it. An O’Hara rule is that all pets must be fed on linoleum. It’s awfully hard to get crunchies out of a shag rug.

I whistled for Charlie and Mouse, our cats, but my sister Carrie came into the kitchen instead.

“Hi!” I greeted her. “You’re home late today.”

“I know,” she replied. S

he began rummaging through the refrigerator before she even took off her coat. “The bus had a flat tire. It took forever to get it fixed.” Carrie carefully set an apple on the kitchen counter, then hung her coat in the closet and put her books on the bench in the back hall.

Carrie sat at the kitchen table taking tiny, neat bites out of her apple. She was ten, two years younger than I, and in her last year at Neuport Elementary School. Although Carrie and I are the closest in age of us four kids, we couldn’t look more different. I have olive skin and brown hair with hazel eyes (the same as Mom and Hopie), and Carrie has fair skin with hair so dark it’s almost black, and deep brown eyes (the same as Dad and Brent). Carrie has a heart-shaped face, while mine is long and thin. Also, Carrie is petite, while I am tall for my age, so that she looks much younger than her age, and I look older than mine.

I poured another glass of juice and sat down across from her. “So?” I said.

“So?” she countered.

“Anything exciting happen today?”

“Tricia Kennedy barfed in gym class.”

“That’s not exciting, that’s gross.”

“It was exciting for the nurse. Tricia barfed all the way down the hall and into the nurse’s office and all over the—”

“Carrie! That’s disgusting.”

“Okay, okay. Did anything exciting happen to you?”

I sighed.

“What?” Carrie crunched loudly on her apple.

“Mr. Landi announced that we’re going to be in a pageant this Christmas.”

“Ohhhh,” said Carrie knowingly, probably remembering last spring when I fainted the morning I had to give an oral report for my social studies class. “Do you have to be in it?”

“Well, Mr. Landi hasn’t given us many details yet, but you know how he is. Mr. Participation.”

Carrie nodded. After a few moments she asked, “Are you having auditions or what?”

“I guess,” I said.

“So be absent the day of the auditions. Tell Mom you think you’re getting the virus back again.”

“Carrie, you’re a genius!” I cried. Last spring I’d gotten a virus that I couldn’t shake. It stayed with me for months, and I’d been hot and achy and irritable all summer, and in fact until just a month or so ago. Now we were wondering if possibly Dad had the same thing, or some form of it, and nobody wanted to put up with his moaning and complaining when they’d just gotten over mine. Anyway, if I told Mom I felt it coming on again, I could probably get away with at least two days in bed.

Carrie smiled smugly at me.

“But wait,” I said. “Maybe it would be worse if I stayed home. What if Mr. Landi cast me in some gigantic role? I wouldn’t be able to defend myself.”

“Yeah.” Carrie looked thoughtful.

The two of us sat and schemed so long and so intently that Brent scared us out of our wits when he banged through the back door, Charlie and Mouse frisking ahead of him.

We jumped a mile.

“Brent!” Carrie shrieked.

“What’s wrong? You look like you saw a ghost. Your hair’s standing on end.”

“It is not,” said Carrie, but she patted her hair, checking, when she thought Brent and I weren’t looking.

“Geez, she’s gullible,” muttered Brent from within the refrigerator. He emerged with a carton of milk.

“Well, you egg her on,” I complained. “And don’t drink that out of the container. Get a glass.”

Brent got a glass and sat down at the kitchen table.

Carrie sat across from him dejectedly. Sometimes she has a hard time being the middle sister. She’s mature enough so that Hope and I both look up to her, yet young enough to be pretty gullible at times. Brent has a real knack for getting under her skin.

Mouse and Charlie twined themselves lovingly around my ankles, reminding me that it was almost their dinner time. I picked Charlie up and cradled him in my arms, listening to his rumbly purrs.

Charlie was my special cat, a ginger-colored tiger. In fact, he was everybody’s favorite, except Hope’s, since Mouse wasn’t very loving. For some reason, Hope particularly liked Mouse. Anyway, I found Charlie two years ago. He was a tiny lost stray, mewing weakly inside a cardboard box. Someone had dumped him by the side of the road. So I brought him home and we kept him. It was as simple as that.

I gave Charlie a kiss on his furry orange face and set him on the floor with Mouse. “Carrie,” I said, “why don’t you feed the animals? Brent and I will start dinner. Does anyone know what time Dad’s doctor’s appointment is? Maybe he’ll be home early.”

“Don’t know,” said Brent vaguely. He swallowed the last of his milk.

I checked my watch. Almost five. Everyone would be home in a little over an hour. I put the chicken in the oven and washed the broccoli, while Brent scrubbed the potatoes and stuck them in a pan on the rack below the chicken. Carrie fed Fifi, Charlie, and Mouse. Then we sat at the dining room table and started our homework. We made a warm, peaceful, late-autumn scene, and I began to relax and forget about the winter pageant.

It was five forty-five when the phone rang in the kitchen.

“I’ll get it!” yelled Carrie, but I beat her to it. I was hoping it was Denise Petersen, home from her piano lesson. She wasn’t in my class, and I wanted to tell her about Mr. Landi and the pageant.

“Hi,” I said expectantly when I picked up the phone.

“Liza?” asked the voice on the other end.

“Oh, Mom,” I said, embarrassed. “Sorry. I thought you were going to be Denise. Do you have to work late tonight?” That was her usual reason for calling at this hour.

“Nooo …” she replied slowly. “I’m … at Dr. Seitz’s office with Dad. He’s …” (another long pause) “… still looking at your father. Running a bit late. Would you ask Brent to pick up Hope now? Dad and I won’t be home for awhile.”

“Is something wrong?”

“Just a little delay,” said Mom.

“Mo-om.”

“Liza, what is it?” asked Brent. He was standing behind me and must have been listening to my end of the conversation.

“Talk to Mom,” I said, thrusting the phone at him. I crossed my arms and leaned against the kitchen table.

Brent’s end of the conversation went like this:

“Mom? Hi. What’s up? … Several hours? … Sure. I’ll get Hopie. We started dinner. … You don’t? We could warm it up for you later. … Oh, okay. Everything all right? … Oh … Oh … Okay. See you. ’Bye.”

I pounced on Brent as soon as the phone was back in its cradle. “What’d she say?”

“For us not to worry and for me to pick up Hopie.” Brent grinned. He’s almost a year older than most of the juniors at Neuport High and gets a big kick out of being able to drive already. “And for us to go ahead and eat, and not to save dinner for them.”

“Is that everything?” I pressed.

“Liza.” Brent fixed his brown eyes sternly on me.

“Okay, okay.” I know when to give in.

“Anyone want to come with me to get Hopie?” asked Brent with forced cheerfulness.

“Me!” cried Carrie, dashing into the kitchen.

I was pretty sure she’d heard every word Brent and I had said during the last few minutes, but she didn’t ask one question, at least not before she and Brent left.

It wasn’t until I was standing alone in the dark, empty front hall of 25 Bayberry, watching the headlights of our Toyota carefully inch their way backward down the long driveway, that I began to wonder why Mom was with Dad at Dr. Seitz’s. She never left her office before six o’clock, not unless there was an emergency or a matter of extreme importance. Besides, since when did Mom go with Dad to the doctor? She didn’t even go with Brent or me anymore.

Something was wrong. I could feel it.

Something was very wrong.

Chapter Two

WHEN HOPE ARRIVED HOME that evening, Brent and Carrie and I didn’t even tell her wh

ere Mom and Dad were, just that they were out. Hope wasn’t suspicious. Her parents went out often, and her big brother and sisters baby-sat for her often. Besides, she was all wound up about school.

While Brent parked the car in the garage, Hopie ran in the back door and found me in the kitchen. She grabbed me around my knees, and craned her neck back to look up at me.

“Hi, Liza!” she cried joyously.

“Hiya, Sissy,” I said, leaning over to kiss the top of her head.

Hope has a variety of nicknames—Sissy, Tink (for Tinker Bell, Hope’s favorite Peter Pan character), and Emmy. (Emmy is short for Emily, which is actually Hope’s first name. Dad is the only one who calls her Emmy, though. It’s his special name for her, since Emily was the name of his favorite grandmother.)

“Guess what,” said Hope, wriggling with excitement.

“What?” I bent down to unzip her jacket.

“We made snowmen today. Not real ones, cotton ball ones. I had to leave mine at school to dry. But I made a picture of a snowman, too. Carrie has it.”

Carrie came into the kitchen carrying a big piece of paper which had been rolled up and fastened with a rubber band.

“Let’s see,” I said.

We opened it up and spread it on the kitchen table.

It was hard to make out, since Hopie had used white paint on white paper, but sure enough, there was a wobbly snowman with stick arms and a great big red hat.

“Wow, Sissy, that’s pretty,” said Carrie encouragingly.

“It certainly is. I think we should put it up so everyone can see it.”

“Oh, goody,” said Hopie. “I’ll get the tape.”

We gave the snowman a place of honor on the refrigerator. Hopie chattered on and on about school. They’d taken a walk to the playground, they’d made their own play dough out of salt and water and flour, they’d learned a song about a teapot.

By the time we sat down to dinner, Hope was running out of things to say. Brent and Carrie and I tried to keep a conversation going, but we were struggling. I’m not sure that Hope noticed anything was wrong. She was so delighted with her potato in its jacket, and had to concentrate so hard in order to eat her chicken leg, that she didn’t pay much attention to the rest of us.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

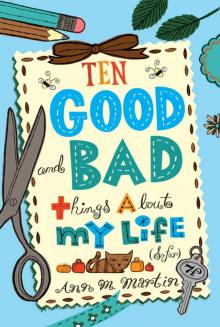

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

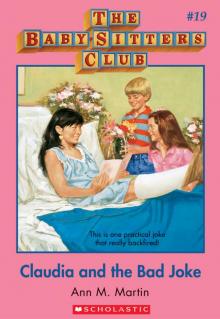

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

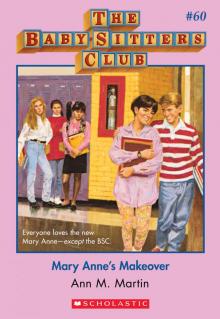

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

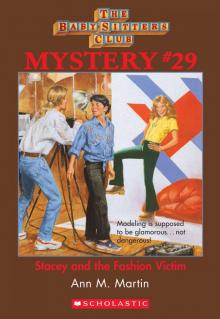

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

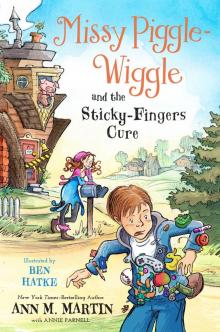

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030