- Home

- Ann M. Martin

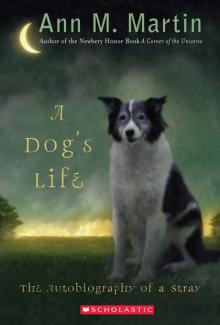

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Night

Part I

The House in the Country

The Wheelbarrow

Mother

Secret Dogs

The Highway

Bad Dogs

The Throwaways

Part II

Squirrel Alone

On the Move

The Fight

Healing

Town Dogs

The Long Winter

Moon

Part III

Gentle Hands

Summer Dog

Farm Dog

The Scent of Bone

Part IV

Old Woman

Addie

Companions

Two Old Ladies

Home

Acknowledgments

After Words™

About the Author

Q&A with Ann M. Martin

If You Love Animal Stories …

Ways You Can Become Involved

Copyright

The fire is crackling and my paws are warm. My tail, too, and my nose, my ears. I’m lying near the hearth on a plaid bed, which Susan bought for me. Lying in the warmth remembering other nights — nights in the woods under a blanket of stars, nights spent with Moon, nights in the shed when I was a puppy. And the many, many nights spent searching for Bone. The fire pops and I rise slowly, turn around twice, then a third time, and settle onto the bed again, Susan smiling fondly at me from her armchair.

Warmth is important to an old dog. At least it is to me. I can’t speak for all dogs, of course, since not all dogs are alike. And most certainly, not all dogs have the same experiences. I’ve known of dogs who dined on fine foods and led pampered lives, sleeping on soft beds and being served hamburger and chicken and even steak. I’ve known of dogs who looked longingly at warm homes, who were not invited inside, who stayed in a garage or a shed or under a wheelbarrow for a few days, then moved on. I’ve known of dogs who were treated cruelly by human hands and dogs who were treated with the gentlest touch, dogs who starved and dogs who grew fat from too many treats.

I’ve known all these dogs, and I’ve been all these dogs.

Lindenfield in the wintertime was a bleak place. The air was chill. For weeks on end a dog could see her breath all night long, and all day long as well. Even in early spring, as winter faded, the gardens, tended by humans in warm weather, were barren and silent. And the lakes and ponds were gray, and very still. No frogs croaked, no turtles sunned, no shiny fish twined through the underwater grasses. In warm weather, things would be different. The air would hum with insect noises, and the ponds might be quiet, but they were rarely silent. Along their muddy bottoms and on their banks and in the moss and grasses and fallen logs was a secret animal neighborhood.

On the piece of land where the Merrions’ big house rose from among gardens and walkways were all sorts of animal neighborhoods. At the time I lived there, as a pup, there were the stone-wall neighborhoods and the shed neighborhoods and the garden neighborhoods and the forest neighborhoods and the pond neighborhoods and the above-the-ground neighborhoods. There was even a secret in-the-Merrions’-house neighborhood. All were linked to form an animal world with the Merrions’ house at the center, like a stone that had been tossed in a pond. The farther the ripples spread from the splash, the more animals were to be found, and the noisier and less secretive their lives were.

The time that I am talking about was not so very long ago, and yet it’s my whole life ago. I haven’t been back to the Merrions’ house since the day I followed my brother off their property. In all my wandering I never found my way back there, but then of course, I was looking for Bone, not for the Merrions.

I really don’t know much about the Merrions. I was very young when I lived on their land, and I was concentrating on what I needed to learn from Mother. But the Merrions couldn’t be ignored. This is what I do know about them:

Their grand house, the house that was the center of our world, was not the center of the Merrions’ world. In the spring, when Bone and I were born — in an old garden shed, the one with the unused chicken coop at the back — the Merrions lived in their house sporadically. They were not like most animals I knew, returning to their nests or burrows or holes night after night or, like the owls, day after day. Instead, they would arrive at the house, always in the evening, stay for a couple of days, then pile back into their car, drive down their lane, and turn onto the big road. Mother would watch as the car became smaller and smaller and finally disappeared. Then several entire nights and days would pass before the Merrions’ car would pull into their lane again.

There were five Merrions in all. I understand that human children generally are not born in litters like puppies, but one or two at a time like deer. The two Merrion parents had given birth to three young. The oldest was a boy, then there was another boy, and finally a small girl, who was the loudest of the children. Over time I learned the names of the children, but only one mattered to me, and that was Matthias, the younger boy, the gentle one. But I did not know him until I was several months old.

The Merrions were tidy people. That was clear. Everything about their house and their property was tidy. The shutters hung straight and were repainted often. No toys littered the yard. The walks and the porches were swept clean, and the gardeners showed up regularly to edge the flower beds, mow the lawns, trim the hedges, and hang potted plants on the porches.

The Merrions did not own any pets. “Because of germs,” Mother once told Bone and me. She had overheard Mrs. Merrion talking to a gardener. “And hair,” Mrs. Merrion had added. “Germs and hair.”

When Mother said this I thought of the in-the-Merrions’-house neighborhood of animals. This consisted not only of many insects, but also of a large family of mice, two squirrels (in the attic walls), a possum who went in and out of the utility room through a hidden hole in the wall, and — in the basement — several snakes, two toads, and some lizards. There were plenty of germs and lots of hair in the Merrions’ house, and this amused me. But I remembered the time I heard screaming and banging and crashing in the house and then Mr. Merrion ran outside with a bag containing a dead, bleeding bat, which he shoved into a garbage can, and I did not feel so amused.

All the creatures on the property knew how the Merrions felt about animals, and they made their own decisions about where to live. Mother had her reasons for choosing the garden shed. There were other sheds and other small buildings on the property, each with its own population, each different from the others, each connected to, but separate from the Merrions.

And that is what I know about the Merrions at the time Bone and I were born. The days were mild — spring arrived early that year — and still the humans came to their home only for brief periods of time. An animal could live quite comfortably on the Merrion property. Around the house were nothing but woods and fields and rolling hills. The nearest neighboring house was a good hour’s trot away, for a grown dog. So the animal communities thrived. There were hawks and moths and foxes and fish and deer and owls and stray cats and frogs and spiders and possums and skunks and snakes and groundhogs and squirrels and chipmunks; birds and insects and nonhuman animals of all kinds.

Apart from Mother and Bone and me, the main residents in our garden shed were cats and mice. There were insects, too, but they were harder to get to know. They came and went and were very small.

The shed was a good place for cats and dogs. Mother chose well when she selected it as the spot in which to raise her puppies. It was a small wooden structure that had originally been built as a chicken coop, the ne

sting boxes still lining one end. The door was permanently ajar, and one window had been removed, which might have made the shed too cold for puppies and kittens. However, when the Merrions bought the big house, they planned to turn the shed into a playhouse for their children, and got as far as insulating two of the walls before Mrs. Merrion decided that a chicken coop was unsanitary and better suited as a garden shed. So the Merrions built a brand-new playhouse and then a bigger garden shed, both sturdier than the chicken coop, and before long, they stopped using the old shed, except as a place in which to store things the gardeners rarely used.

Mother found the shed shortly before she gave birth to Bone and me. She was a stray dog — had never lived with humans, although she had lived around them — and had been roaming the hills and woods bordering the Merrions’ property, looking for the right spot in which to give birth to her puppies. For several days she watched the Merrions’ house from the edge of the woods. She watched the animals on the property, too. There were no other dogs that she could see, but there was a mother fox with four newly born kits, and sometimes, in the small hours of the morning, she heard coyotes yipping in the hills. Mother needed a place that was safe from predators, out of sight of the Merrions, and warm and dry for her puppies.

The shed seemed perfect. The first time she poked her nose through the partially open door she noticed how much warmer the inside air was than the spring air outside. She stood very still, listening and allowing her eyes to adjust to the darkness. She heard the scurrying of mice in straw, but nothing else.

The old nesting boxes for the chickens were along the wall across from the door. Mother had never seen anything like them. She crept forward to investigate. First she surveyed them from several feet away. Then she crept closer, and finally she stuck her nose into one of the holes.

Hssss! Pttt! Something sprang out of the box, hissed and spat at Mother, then ducked inside again. It was a yellow cat, protecting a litter of newborn kittens. Mother backed up and surveyed the boxes from a little distance. Now she could see eyes in several of the holes. More cats. Mother left them alone. She was too big to fit in the boxes anyway. Behind her, along the sides of the shed and next to the door, were a few old gardening tools, some clay pots, a few piles of straw, and a wheelbarrow filled with burlap bags and more straw. The mice had chewed holes in the bags, but the burlap still looked cozy and warm. Mother glanced up. In the rafters above she could see several abandoned nests that had belonged to barn swallows and hornets.

Mother considered the cats again, the pairs of eyes glaring at her from the nesting boxes. And then she heard a tiny rustle behind her. She swept her head toward the door in time to see a large gray cat squeeze through it. The cat stared at Mother, then hurried by her and disappeared into a hole. Mother let out a quiet woof. In response, she heard a soft growl from the cat, but nothing more.

That afternoon Mother sat patiently near the door, watching the comings and goings of the cats. As long as she didn’t move about too much, the cats kept their distance. Mother watched the mice, too. They kept their distance from the cats. When night fell, Mother crept to a pile of straw that was as far away from the cats as she could get. She curled up on it, her back to the nesting boxes, and fell asleep. She was safe, she was very warm, and the night passed peacefully.

In the morning, Mother felt she was ready to give birth to her puppies.

We were born in the wheelbarrow, Bone and I. Mother (her dog name was Stream, but to Bone and me she was simply Mother) managed to climb into it early that first morning, having decided that it was an ideal nest for her puppies.

Mother gave birth to five puppies, but only Bone and I survived. Two of the puppies were born dead, and a third lived for less than an hour. He was tiny, too tiny, and his legs were misshapen. Mother tossed him out of the wheelbarrow and ignored him. He whimpered several times, then was silent.

Bone and I were strong, though. We nuzzled into Mother and nursed from her. We squirmed and wiggled. We slept, our heads curled under our chests, we burrowed, we nursed some more. And when, after our first night, Mother saw that Bone and I were still strong and active and eating well, she gave us our names. She chose, as mother dogs do, names of things that are important to her. So I was known as Squirrel, and my brother was known as Bone.

My earliest memories are of warmth, comfort, and food. For the first days of my life, my eyes and ears were not open. Bone and I slept most of that time, rousing ourselves only to eat. Awake or asleep we curled into our nest, into each other, and into Mother. I could feel the heartbeats of my brother and mother.

During this time, Mother left the wheelbarrow as little as possible, but she did have to leave it. She would rise unsteadily, cover Bone and me in the straw and burlap, climb over the edge of the wheelbarrow, and leave the shed to relieve herself and to find food. She would come back as soon as she could, and then Bone and I would squirm into her.

When Bone and I had been alive long enough for the moon to change from a disk to half a disk, our eyes and ears opened, and my world slowly became clear to me. Head and legs wobbling, I stood in the wheelbarrow and gazed around the shed. The light was dim but I could make out the nesting boxes and later the eyes that peered from within them.

All day long the adult cats came and went. When I wasn’t sleeping, I followed their movements in the shed. The cats trotted back and forth, slinking through the open door. Sometimes they returned carrying small rodents in their mouths, sometimes birds. I watched them take their food back to the nesting boxes. The cats, sleek and lean and almost always hungry, would pause at the boxes and glance around the shed before leaping through a hole. They glanced around the shed before leaving the holes, too. Their glances always took in Mother. The shed cats were not our friends, but I think we trusted one another, even as wary as we all were.

One day, one of the shed cats, the hissing yellow one Mother had met when she first discovered the shed, left her kittens and did not return for a long, long time. By afternoon, her kittens were mewing loudly, so loudly that Mother jumped out of the wheelbarrow and poked her nose in their nesting box. I heard all sorts of spitting and growly noises from the adult cats in the shed, but Mother ignored them. She backed out of the box with a kitten in her mouth and dropped it to the floor. Then she pulled out two more kittens, lay on the floor beside them, and lifted her hind leg in the air. The kittens burrowed into Mother the way Bone and I did, searching for milk.

Creak. Behind us the shed door eased open. Standing in it was the yellow cat. She stared at Mother for a moment, then bolted through the shed. Mother leapt to her feet, the kittens tumbling away, and she scrambled back into our wheelbarrow while the cat collected her babies.

Our shed was busy all day long and all night long, too. Mother and Bone and I tended to sleep at night, but not the cats. And definitely not the mice. The mice were busy and noisy. We could hear them chewing. And climbing. There was no place in the shed the mice couldn’t get to. They scurried up walls and posts and along rafters. They ran in and out of holes too tiny to notice. They emerged from unlikely places — under flowerpots and inside beams. Usually they could outrun the cats or escape from them, but sometimes a cat was smarter or more patient than a mouse, and then with a squeak, and a flash of teeth and claws, the mouse became a meal.

For a long time I felt secure as a dog, even a small one, in our shed. Mother was the biggest creature there, and she didn’t fear the cats or the mice. But my eyes and ears had been open for just a few days when I realized what nearby threat Mother did fear, and that was the fox.

The fox, the one with the four kits, lived underneath the Merrions’ new garden shed. I don’t know where her mate was. I never saw him. And I wouldn’t see the mother or her kits with my own eyes until the time that I was big enough and strong enough to leave the wheelbarrow and go outside. Mother saw the fox often, though. She paid attention to her and she even learned her name. Mother didn’t learn the names of the other creatures on the Merrions�

�� property, but the fox was a different story, and that was because Mother had recognized how dangerous she could be.

The fox’s name was Mine, and I believe she had named herself. Mine wasn’t interested in Mother. And she didn’t know Mother had puppies, so Bone and I were not in danger from Mine. Still, Mother was afraid of her. Bone and I would peer over the edge of the wheelbarrow and see Mother at the door to the shed. She sat planted on her haunches, her brow creased, gazing out at the field beyond the Merrions’ backyard. I could tell when Mine was in the field, because Mother sat at strict, grim attention. If a squirrel was out there, Mother would sit quivering, her tail twitching. She might even jump to her feet and give chase. But when Mine was outside, Mother watched motionless, except for the slow turn of her head as she tracked Mine from a garden to the woods, or from the playhouse to the Merrions’ porch.

This was why Mother feared Mine: Mine had no sense. She didn’t even have the sense to steer clear of the Merrions. She wandered through their yard at all hours, not caring who might see her. She didn’t teach her kits to fear the Merrions, she didn’t try to hide her kills, she was reckless, she was bold, she was cheeky. Mother thought Mine put us all in danger.

I didn’t quite understand this, though, not when I was still such a young puppy that I couldn’t leave our nest. All I knew then was life in our warm wheelbarrow, where each day was much the same as the next. Bone and Mother and I would lie in a pile of fur and feet and tails and snouts. Bone and I would nurse. When Mother left the shed, which she did more often as Bone and I grew older, I would peer over the edge of the wheelbarrow at the cats and mice. I watched the mice dart and hide, listened to them chew and squeak. I watched the cats come and go, listened to them mew and purr. Every now and then a cat or an older kitten would venture out of the shed and not return. I realize now what was happening: The mice were eating corn and seeds, the cats were eating the mice, and owls and hawks were eating the cats.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

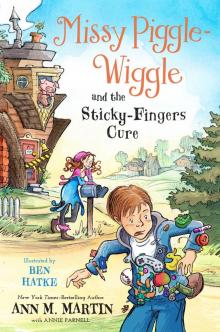

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030