- Home

- Ann M. Martin

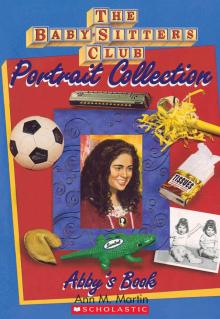

Abby's Book

Abby's Book Read online

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

CHAPTER 1

ME, MYSELF, AND I: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ABIGAIL STEVENSON: FROM BIRTH TO BACKPACK

CHAPTER 2

BED AND BLUE JUST WON’T DO

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

WITHOUT DAD

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

THE SHOOTING STAR

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

NEW PLACES, NEW FACES

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO AVAILABLE

COPYRIGHT

The clock radio woke me at 8:00 A.M. “You’ve heard another fab hour of solid rock and roll,” the deejay announced in a booming voice. “Now for a few words from our sponsors. Bellair’s Department Store is the one-stop shopping center for the whole family … ”

Why is it that my clock radio always wakes me with commercials instead of with some of that solid rock and roll?

I turned over, switched off the radio, and lay back, planning the day ahead. It was Saturday. I was coaching softball that morning. Maybe I’d hit the pizza parlor with Kristy at lunch. Then I had soccer practice in the afternoon. I remembered that my mother and my sister and I were having Chinese takeout for dinner and renting a couple of films. What was I forgetting? Oh, yeah. Homework. Well, that could wait until Sunday. My weekend homework probably wouldn’t take me more than an hour. Now, what was my weekend homework?

Homework! I bolted straight up, wide awake. I had a huge assignment due on Monday. I had to write a book. And I was only planning an hour for homework?! I needed a lifetime. Well, maybe not a lifetime, but I definitely needed more than two days.

I guess you’re wondering what the book is about. The book I have to write is about me — Abigail Stevenson. It’s an autobiography. Now, I bet you wonder why an eighth-grader is writing an autobiography. Frankly, I don’t know. And I don’t approve of asking kids to write the story of their own life. We should be living our lives, not writing about them. I also don’t approve of long assignments. Maybe, I thought, I should go back to sleep for a little while — like all weekend.

My sister, Anna, knocked on the door and stepped into my room. “Abby, Mom made pancakes. If you want some, you should get up.”

“It’s Saturday morning.” I groaned. “What’s the rush?”

“I have orchestra practice at nine and Mom has to work today,” Anna answered.

Anna is my twin. We’re identical twins, but not the type who do everything the same. I’m a jock. I love sports — especially soccer, softball, and running. I’m also outgoing and always cracking jokes. Anna is quieter than I am — by a lot. She’s also a musician, which I am not. Anna can play a load of instruments, including the harmonica and the piano. She’s best at the violin, which is her favorite instrument.

People used to mix Anna and me up and call us by each other’s names. But not anymore. We don’t dress alike — ever. We both have curly black hair but Anna wears her hair short and I wear mine long.

“I didn’t know Mom was going to the city today,” I told Anna.

“She’s meeting one of her writers,” Anna explained. “Come on. The pancakes will be cold.” Anna went downstairs and I got dressed.

We live in Stoneybrook, Connecticut, but our mother goes to Manhattan every day to work. She’s an executive editor at a New York publishing house. You’d think since my mother edits books I wouldn’t mind writing one. Forget it.

I walked into the kitchen just as Mom set a plate of blueberry pancakes at my place. I set a pile of papers and photos next to the plate.

“What’s all that?” my mother asked.

“Research,” I said. “For my autobiography. I thought I’d ask you a few questions during breakfast.”

My mother checked her watch. “I’m out of here in five minutes. One of my authors has a big book signing today. I’m taking her to lunch.”

“Well, I’m an author too,” I said. I pretended to be a news announcer. “Ms. Abigail Stevenson, known for her best-selling autobiography entitled … ” I hesitated. I needed a title. It came to me like a spark of genius. “ … entitled Me, Myself, and I.” I flashed a newscaster’s toothy smile at my audience. “It’s a touching book, a funny book, and best of all a short book.”

My audience of two laughed. But not for long.

“Seriously, Abby,” my mother said, “how’s the autobiography coming along? It’s due on Monday, isn’t it?”

I pointed a forkful of pancake at my notes. “I have lots of ideas,” I said. “I just have to pull them together, add a few pics, and whammo! My masterpiece is done.”

My mother turned to Anna. “You turned yours in last week.”

“Only because it was due a week earlier than Abby’s,” Anna explained.

Every eighth-grader at Stoneybrook had to write an autobiography. Which was a good enough reason for me to wish that we’d moved from Long Island to Stoneybrook when I was in ninth grade instead of eighth.

I flipped through my notes and asked Mom questions about my childhood while we ate. I was still asking her questions as she climbed into our minivan to drive to the train station.

After my mother drove away, I stood in the driveway thinking about the interesting fact she’d just told me. Though Anna is older than me by eight minutes, I took my first steps a few hours before she took hers. I wondered if that was why I became more athletic than Anna. Or did I walk independently first because I already was more athletically inclined?

Kristy Thomas came running up to me from the sidewalk. “Hi,” she said. “You ready? We’ll be late for practice. Get your glove. We better book it.”

“Book it?” I said. “I’m booking it, all right.” I held up the notebook I’d been using for my interview with my mother. “Autobiography. All weekend. I am seriously bummed.”

“Too bad,” said Kristy. She gave me a little punch on the arm. “Good luck.” She went off.

“Thanks,” I yelled. Of all my new friends, Kristy’s the one who’s most like me.

We’re both outgoing and smart. (Even though I don’t like homework — or writing books — I am pretty smart.) And we both love sports. Kristy coaches a softball team for little kids called Kristy’s Krushers. I’m her assistant coach.

There are ways Kristy and I are different too. Kristy is more organized than I am and much bossier. However, her bossiness can be a plus. You see, Kristy is the president and brains behind this great club I belong to, the Baby-sitters Club (or BSC).

Here’s another way Kristy and I are different. She comes from a huge blended family. In my family it’s just Anna, my mom, and me. Our dad died in a car accident when Anna and I were nine. I still miss him and think of him every single day. Kristy lost her dad too. Only in Kristy’s case, her father ran away.

I’m not the only BSC member who’s experienced the death of a parent. Mary Anne Spier’s mother died when Mary Anne was an infant. After Mary Anne’s mother died, her family was even smaller than mine — there was only her and her dad. That changed when Mr. Spier married his high school sweetheart and they brought their two families together. Now Mary Anne has a stepmother, a stepbrother, and a terrific stepsister, Dawn Schafer, who is an honorary member of the BSC. Right now, Dawn is living in California with her father and brother. But she comes to visit, so I’ve met her. I can see why Mary Anne and the other members of the club miss Dawn. She’s really cool.

Mary Anne is the secretary of the BSC. She keeps track of our baby-sitting jobs in the club record book and makes sure that we a

ll write in the club notebook. Mary Anne is the perfect person for that job because she is super-neat and super-conscientious.

Our treasurer is Stacey McGill. Stacey loves math and is excellent at it. That girl knows just where to put a decimal point. She also knows how to dress.

Stacey and I have something major in common. We both suffer from annoying, chronic illnesses. (A chronic illness is one that doesn’t go away.) Stacey’s chronic illness is diabetes. She can’t eat desserts or sweets. She has to check her blood and give herself insulin injections every day.

I have allergies and asthma. I’m allergic to lots of foods, such as milk products and shellfish. I’m also allergic to most stuff that floats through the air — dog hair, dust, and pollen. The allergies and asthma are connected. They both affect my ability to breathe, especially the asthma. I use an inhaler when I feel an asthma attack coming on, but I still land in the hospital a couple of times a year. Not being able to breathe is pretty scary.

I don’t make a big deal about my illnesses. (Neither does Stacey.) I refuse to let it get me down or to keep me from doing the things I love, such as sports. I think I’ll outgrow some of my allergies and hope the asthma might just disappear too.

The vice president of the BSC is Claudia Kishi. Claudia is really cool. I love her kooky way of dressing. Yesterday, for example, she wore leopard-skin tights with a black velvet minidress to school. Her earrings were made out of fake-fur buttons. (She made them herself.) Claudia is what you’d call a theme dresser, and yesterday the theme was “jungle.”

We have our club meetings three times a week (Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays) in Claudia’s room, which is equipped with a private phone line — perfect for our BSC calls — and an inexhaustible supply of junk food for our personal pleasure.

The BSC has two other regular members, Mallory Pike and Jessi Ramsey. They are both sixth-graders and junior officers of the club. Mal and Jessi are best friends.

Mal loves literature and wants to write and illustrate children’s books. She can’t wait to be an eighth-grader and write her autobiography. It’ll be a snap for Mal.

Jessi is a fabulous ballet dancer. She studies ballet as seriously as my sister studies the violin, which is very seriously!

The BSC also has two associate members, Logan Bruno and Shannon Kilbourne. Associate members fill in when the BSC has more jobs than the regular members can handle. Logan and Shannon don’t have to come to the meetings all the time like the rest of us. By the way, Logan is Mary Anne’s boyfriend, and Shannon and my sister are close friends.

So that’s the BSC and my new group of friends. I still miss my friends from Long Island, where I lived before moving here. Except for having to write the story of my life, I love living in Stoneybrook, Connecticut.

Anna appeared beside me on the driveway. “Penny for your thoughts,” she said.

“I’ll tell you for a buck fifty,” I said with a grin.

“I’m saving my money to buy your book,” she quipped.

“I guess I have to write it if I’m going to make the best-seller list.”

“I guess you have to write it if you’re going to pass English,” Anna pointed out.

Anna went to orchestra practice and I went to my room. It was time to work on my autobiography. It was a story that no one could write but me, myself, and I.

“I was so big with the two of you,” my mother told me, “that I couldn’t even think of unpacking those boxes. Since you weren’t due for a month, your father and I thought there would be plenty of time for him to settle us in the new place when he came back from his trip. So there I sat on October fifteenth — big as a house in the middle of this mess — trying to imagine what it would be like to have identical baby girls. That’s when I realized you were going to be born a lot sooner than we thought.”

Mom phoned our dad at his environmental engineering meeting in Chicago. He left the meeting immediately to catch the first flight back to New York. Next, Mom called her doctor and described how she felt. The doctor told her to have someone drive her to the hospital right away. Since Mom didn’t know any of her neighbors yet, she called a car service.

The guy who drove her was pretty nervous. “You think you’re going to have that baby in the car, ma’am?” he asked.

“Babies,” Mom said, correcting him. “I’m having twins.” The poor man almost drove onto the lawn when he heard that!

Mom didn’t have us in the car, though. And our dad walked into the delivery room just as Anna was being born.

Eight minutes later I popped into the world.

“Some people don’t think newborns are cute,” my father used to say. “But you girls were beautiful from the get-go.”

Mom says that when she came home from the hospital with Anna and me, the whole apartment was set up. Dad had unpacked everything and put it away. And the nursery was perfectly furnished and decorated. Dad had bought and put up the balloon-patterned curtains Mom had admired in the store, but that they’d put off buying. He had also hung two fish mobiles over our new cribs.

“On top of everything else he did,” she said, “he surprised me with a rocking chair for your room.”

That’s the kind of man my dad was. Thoughtful and generous.

I asked Mom if it was hard to raise two babies at the same time. “It was difficult,” she said. “But after a few months, you entertained one another. If one of you was fussing, I’d put her in the crib with the other one, and the fussy baby would quiet down. That was a big help.”

One of my first memories is of thinking I was looking at Anna when I was actually seeing myself in the mirror. It took me a long time to tell the difference between my sister and my own reflection.

Another early memory I have is being with my dad and Anna at a playground. Anna and I were playing on the slide. Dad was standing at the bottom to catch us. I’d just slid down and was waiting with him at the bottom of the slide for Anna. Suddenly a bully at the top of the slide pushed past Anna and she tumbled to the ground.

Dad ran to her. I crumbled where I stood and started crying. I thought I’d been hurt too. Dad had two crying kids to deal with. One really hurt (Anna sprained her ankle) and the other one thinking she was hurt.

He had to carry both of us home. I remember my ankle truly hurting, and I insisted on having an Ace bandage just like Anna’s.

Because Anna and I mostly played at home with one another, we didn’t know for the first few years of our lives that being an identical twin was unusual.

When we were three years old, Mom and Dad decided that we should learn to play with other kids. So, after our third birthday, they enrolled us in a pre-school.

While Anna was meeting the teacher, I checked out the playroom for twins. But I couldn’t find any pairs of identical kids other than Anna and me.

My mother called to me. I was in the block corner. I could see her over the top of the block pile, but my sister was blocked (get it?) from my view. I panicked. Was this a place where half of you — your twin — disappeared?

I started screaming, and my mother and Anna came running to me. Because I was crying, Anna started crying too. Only Anna and I understood what had upset me. And at that age we weren’t very good at explaining things to other people.

You see, Anna and I had developed our own private language for communicating between ourselves. Because we understood one another so well, we didn’t bother to learn to speak English as quickly as most kids do. I’ve heard this happens a lot with twins. I can’t remember any of the words of our secret language now. Neither can Anna.

It was because of our language that our parents decided to send us to pre-school. And sure enough, it worked. There were lots of interesting things to do there, and plenty of kids we wanted to talk to. We learned to speak English very quickly.

Our teacher, Ms. Randolph, loved having identical twins in her class. “You girls are so cute,” she used to say. She didn’t even mind that she could barely tell us apart.

&n

bsp; Even though we dressed alike, Anna and I were already interested in different activities. Anna liked musical instruments and I always begged to play outdoors on the jungle gym.

By the end of each day, Ms. Randolph had an easier time telling us apart. I was the dirty twin and Anna was the one in the corner playing with the plastic guitar.

Here’s one of the things I didn’t like about being twins. People stare at you. Even now, when Anna and I dress differently and have different hair styles, strangers often stare when they see the two of us together. They’ll say something brilliant like, “You two are twins, aren’t you?”

When we were very little, perfect strangers would talk to us. They’d say we were adorable and ask our parents, “However do you tell them apart?”

Most of the time Anna and I hated it when someone made a big deal out of our twin-ness. Anna would duck her head and not look at the person. But I’d stare right back. Sometimes I’d make a silly face. If the person said “And what’s your name?” I’d answer for both of us.

Sometimes I’d reverse us and say, “I’m Anna and she’s Abby.” My dad would wink at me to let me know that he knew who was who. After the person left, we’d laugh about our joke.

* * *

One day, when we were five years old, we were at the mall with our mother when we noticed another set of identically dressed twins walking across the center court, carrying identical shopping bags. They were women about the age of our grandmothers. When the twins spotted us, they hurried over to us.

“Well, well,” one of them said.

“Look at these girls,” said the other. Their voices and expressions were identical too.

“I’m Jan Sanders,” said one.

“I’m Jean Sanders,” said the other.

My mother introduced us. Even though I wasn’t usually shy, for some reason I felt shy in front of the Sanders twins.

“Do you always dress alike?” my mother asked them.

“My, yes,” answered both twins with a laugh.

They held up their identical shopping bags. “Sweaters,” said Jan.

“We live in identical houses next door to one another,” said Jean. Or was it Jan? I’d already lost track of which was which.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

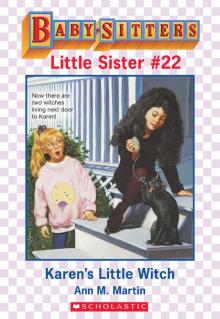

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030