- Home

- Ann M. Martin

A Corner of the Universe

A Corner of the Universe Read online

Praise for

ANN M. MARTIN’S

A Corner of the Universe

“Martin hints at a life-changing event from the first paragraph of this novel narrated by a perceptive and compassionate 12-year-old.… Hearts will go out to both Hattie and Adam as they step outside the confines of their familiar world to meet some painful challenges.”

— Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Martin delivers wonderfully real characters and an engrossing plot through the viewpoint of a girl who tries so earnestly to connect with those around her. This is an important book.”

— School Library Journal, starred review

“Martin’s voice for Hattie is likable, clear, and convenient; her prose doesn’t falter. A solid, affecting read.”

— Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“Martin’s characters shine.… This is a fully realized roller coaster of emotions, and readers take the ride right along with Hattie.”

— Booklist, starred review

“Martin excels at evoking simply the intricacies of friendship, what it enables you to give others, and what it teaches you about yourself. She also understands its perils.… [This is] the kind of novel kids mean when they ask for ‘a book about friends.’”

— Horn Book, starred review

“Martin deftly regulates Hattie’s growing expressiveness .… Her perspective on her own universe is well captured and affecting.”

— The New York Times Book Review

“A Corner of the Universe transports us back to a simpler time and place — a Midwest town in 1960 — but reminds us that family life is never as simple as it might appear .… In spare prose, Martin draws a sympathetic portrait of a smart, sensitive girl not yet sure she wants to leave childhood. Universe never succumbs to stereotype or melodrama. It tells an emotional story simply and directly.”

— USA Today

A Newbery Honor Book

A Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year

A BookSense Top Ten Pick

An ALA Notable Book

A Booklist Editor’s Choice

A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book

A New York Public Library Best Book for Reading and Sharing

A New York Public Library Best Book for the Teen Age

Table of Contents

Cover

Praise

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Ninteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Author’s Note

After Words

About the Author

Q&A with Ann M. Martin

The 1960 Universe

The Amazing Day Finder

Copyright

Last summer, the summer I turned twelve, was the summer Adam came. And forever after I will think of events as Before Adam or After Adam. Tonight, which is several months After Adam, I finally have an evening alone.

I am sitting in our parlor, inspecting our home movies, which are lined up in a metal box. Each reel of film is carefully labeled. WEDDING DAY — 1945. VISIT WITH HAYDEN — 1947. HATTIE — 1951. FOURTH OF JULY — 1958. I look for the films from this summer. Dad has spliced them together onto a big reel labeled JUNE–JULY 1960. I hold it in my hands, turn it over and over.

The evening is quiet. I feel like I am the only one at home, even though two of the rooms upstairs are occupied. I hear the clocks in Mr. Penny’s room, and footsteps padding down the hall to the bathroom. The footsteps belong to Miss Hagerty, I’m sure of it. I know the routines of our boarders, and now is the hour when Miss Hagerty, who is past eighty, begins what she calls her nightly beauty regime. Outside, a car glides down Grant Avenue, sending its headlights circling around the darkened living room. It’s warm for October, and so I have cracked one window open. I can smell leaves, hear a dog barking.

Mom and Dad have gone with Nana and Papa to some big dinner at the Present Day Club, their first true social event since Nana and Papa’s party on that awful night in July. On this first night to myself, Dad has entrusted me with his movie projector and all the reels of film. I made popcorn and am eating it in the parlor where technically I am not supposed to eat anything, following the unfortunate deviled egg incident of 1958. Really, you can only see the edges of the stain, plus I’m twelve now, not some little ten-year-old. I would think the food ban could be lifted, since Dad feels that I am responsible enough to operate his movie equipment.

He said I could do everything myself this evening, and I have, without a single mistake or accident. I set up the screen at one end of the parlor. I lugged the projector out of the closet, hoisted it onto a table, and threaded it with a reel of film, making all the right loops. Turned on the projector, turned off the light, put the bowl of popcorn on a pot holder in my lap, and settled in to watch the film labeled HATTIE — 1951. It’s one of my favorites because my third birthday party is on it and I can watch our old cat Simon jump up on the dining room table and land in a dish of ice cream. Then I can play the film backward and watch Simon fly down to the floor and see all the splashes of ice cream slurp themselves back into the dish. I made Simon jump in and out several times before I watched the rest of the film.

But now I am holding the tin from this summer. I consider it for a long time before I take out the reel and fasten it to the side of the projector. I thread and loop and wind, doing everything by the light of a little reading lamp. When I finish, my hands are shaking. I draw in a deep breath, turn on the projector, turn off the light, sit back.

Well. There is Angel Valentine, the very first thing. She is standing on our front porch, waving at the camera. We have an awful lot of shots of people standing on our front porch, waving at the camera. That’s because when Dad pulls out his camera and starts aiming it around, someone is bound to say, “Oh, Lord, not the movie camera. I don’t know what to do!” And Dad always replies, “Well, how about if you just stand on the porch and wave?” So there is Angel waving. Pretty soon Miss Hagerty and Mr. Penny step out of the house and stand one on each side of Angel and they wave too.

And then later, on another day, in dimmer light, I see Nana and Papa standing on their own front porch, waving. They are dressed for a party. Papa is in his tux with shiny shoes, and Nana is wearing a long dress, all the way to her ankles, a shawl wrapped around her shoulders. I don’t remember where they were going, dressed like that. But they are happy, smiling, their arms linked, Papa patting Nana’s hand.

And then suddenly there is Adam. He won’t smile or wave at the camera. He would never do anything you asked him to do when the movie camera was out. So he is standing in our yard tossing a baseball up and down, up and down. When the front door opens and Angel steps out, looking fresh and cool in a sleeveless summer dress, he drops the ball at his feet and stares at her as she waves at Dad, then sits on the porch swing and opens a book. I play the scene backward, then watch it again. Not for the entertainment value, but so I can see Adam once more.

Next comes the carnival. I sit up straighter. There’s the Ferris wheel. Mom and I are riding it around and around, feeling awkward because Dad won’t turn off the camera. We smile and smile and smile some more, huge smiles that eventually begin to look branded onto our faces. And there’s the Fourth of July band concert, our p

icnic spread in front of us. Adam is eating in a machine-like way, refusing to look at the camera. Everyone else dutifully makes yummy motions, pats their stomachs, grins in Dad’s direction. I let out a quiet burp, for Adam’s benefit, which makes him laugh.

Finally there is my birthday party — the one Mom and Dad gave, not Adam’s. Adam’s was private. And it was a once-in-a-lifetime event. This party is the one we have every year. I look at the cake, the presents. No Simon now. He died when I was five, and we never got another pet. Everyone is laughing — Mom, Nana, Papa, Cookie, Miss Hagerty, Mr. Penny, Angel, me. Everyone except Adam, who is focused on the decorations on my cake. We don’t know it yet, but this is the beginning of the sugar rose incident, and Adam is about to storm off and Dad is about to stop filming.

Presently the reel clicks to an end and the tail of the film flaps around. I turn the projector off and sit in the dark for a few moments, thinking about all those happy images. The smiling, the waving. I want to cry. My father’s movies are great, but they don’t begin to tell the story of the summer. What’s left out is more important than what is there. Dad captured the good times, only the good times.

The parts he left out are what changed my life.

On early summer mornings, Millerton is a sleepy town, the houses nodding in the heavy air. Not even six-thirty and I can feel the humidity seeping through the window shades and covering me like a blanket. Everything I touch is damp.

I’m pretty sure I am the only one in the house who is awake. I lie in bed for a while, listening to the birds. I’m not about to spend the morning in bed, though, even if it is the first day of summer vacation. Some of my classmates wait all year long for summer just so they can sleep late every morning. Not me. I have way too much to do. I roll out of bed, dress in shorts and sandals and the sleeveless blouse Miss Hagerty made for me on her Singer sewing machine. The blouse is white with a big X of blue rickrack across the front.

I tiptoe down the hallway. My room is at one end, the staircase at the other. In between are my parents’ room, Miss Hagerty’s room, Mr. Penny’s room, Angel Valentine’s room, a small guest room, a bathroom, a powder room. (It is a long hallway.) It must be 6:45, because just as I pass Mr. Penny’s room, it erupts with chiming and clanging and peeping and chirping. Mr. Penny used to run a clock repair shop. He’s retired now, but his room is filled with clocks, and of course they all run perfectly. At quarter past, half past, and quarter to every hour, they ding and cheep and whir, sounds we have all grown used to and can sleep through at night. On the hour itself, cuckoos pop out of their wooden houses, one clock chimes like a ship’s bell, animals waltz, skaters glide. Mr. Penny even has a grandfather clock, which I think he should have, since he could be a grandfather if he had ever had any children. A sun and a moon move across the face of that clock. And even though Mr. Penny is not one for kids (not now, never has been), he lets me wind it with the little crank once a week, keeping my eye on the weights inside until they are in just the right position. Mr. Penny says I am responsible.

I tiptoe down the stairs and into the kitchen. I am still the only one up. This is good. If I’m going to start breakfast for everyone I like to have the kitchen to myself. I set out some of the things Cookie will need when she arrives. Cookie is our cook and she helps Mom with the meals for our boarders. Her real name is Raye Bennett, which I think is beautiful, a name for a heroine in a novel, but everyone calls her Cookie, so I do too. I sometimes wonder if she wouldn’t like to be called Raye or Mrs. Bennett, but nobody in our family asks too many questions.

In the summer I am in charge of Miss Hagerty’s breakfast tray. Miss Hagerty is the only one of our boarders who takes breakfast in her room. This is primarily because she is old, but also because oh my goodness no one must see her before she has had a chance to put her face on, and she needs energy for that job. So every morning I make up her tray, which is always the same — a soft-boiled egg in a cup, a plate of toast with the crusts cut off, and a pot of tea. Since Miss Hagerty appreciates beauty, I put a pansy in a bud vase in the corner of her tray.

Seven-fifteen now, a key in the front door, and suddenly the kitchen comes alive. Cookie bustles in at the same time Mom and Dad stumble downstairs. My parents are still in their pajamas, smelling of sleep, and in Dad’s case, of Lavoris mouthwash.

“Good morning,” I say.

“Good morning!” cries Cookie, always cheerful.

“Morning,” mumble Mom and Dad.

Mom collapses onto a kitchen chair. “Hattie,” she says, “you’ve already fixed Miss Hagerty’s tray?”

Well, yes. I am holding it right in front of me.

“She’s industrious,” says Cookie, who has opened four cupboards, taken the carton of eggs out of the refrigerator, and turned on the fire under the skillet. “Like me.”

I am pleased by Cookie’s comment, but I don’t know what to say, so I say nothing.

Mom considers me. “She could be a little less industrious and a little more outgoing.”

I stalk out of the kitchen, the moment ruined. I would like to stomp up the stairs, but I can’t since I am carrying the tray and I don’t want to slosh tea around.

I knock at Miss Hagerty’s door.

“Dearie?” she calls. For as long as I have known Miss Hagerty (which is all my life, because she has lived in our boardinghouse since before I was born), she has never called me anything but Dearie. When I was little, I thought maybe she couldn’t remember my name. But I notice she doesn’t call anyone else Dearie, so I am pleased that it is her special name for me.

“Morning, Miss Hagerty,” I call back. “Can I come in?”

“Entrez,” she replies grandly.

I balance the tray on one hand and open the door with my other. I am just about the only person who is allowed to see Miss Hagerty early in the morning before she has put her face on. And she is something. She is propped up in bed, a great perfumy mountain. Some of the mountain is Miss Hagerty’s astonishing bedding — floral sheets and quilts and lace-edged pillows, woolen throws that Miss Hagerty and her friends knitted. She sleeps under the same mound of bedding whether the temperature is 90 degrees or 20 degrees. The rest of the mountain is Miss Hagerty herself. Miss Hagerty reminds me of her bedding — soft and perfumed, her plump body always draped in floral.

I place the tray on Miss Hagerty’s lap. She prefers to eat her breakfast in bed. I draw back her curtains, then sit in an armchair and look around. There is barely a free inch of space in Miss Hagerty’s room. The sewing table is piled high with fabric. From her quilted sewing bags spill cards of lace and bias tape, buttons and needles and snaps. Every other surface of the room is covered with perfume bottles, china birds, wooden boxes, and glass bud vases.

Neatly arranged on her dresser are twelve framed photos of me, one taken on the day I was born, and the others taken on each of my birthdays since then. I see myself change from a chubby baby to a chubby toddler to a skinny little girl to a skinny older girl, watch my hair lighten to near white, see the curls fall away to be replaced by braids. I think the photo mirror is a great honor. Miss Hagerty says she considers me her granddaughter. And I wish she were my grandmother. That has to be a private wish, though, since I already have two grandmothers. It’s just that Granny lives in Kentucky and I hardly ever see her, and Nana … well, Nana is Nana.

“Miss Hagerty,” I say while she begins the process of slathering the toast with the egg, which she has mushed up in its cup, “what’s wrong with being shy?”

“Nothing at all, Dearie. Why?”

“I don’t know.” I can’t quite look at Miss Hagerty.

“Well, don’t you worry about getting a boyfriend. Trust me, even shy girls get boyfriends.”

That was the last thing on my mind, but it is a fascinating thought. Almost as fascinating as the fact that Miss Hagerty, never married herself, is practically an expert on boyfriends and husbands. Not to mention on hairstyling and makeup. She is always saying things to me like, “De

arie, you could soften those sharp cheekbones of yours with a little blush — right here.” Or, “Look, Dearie, how this eyeliner will make your gray eyes spring to life.” I am not allowed to wear makeup yet, but I store up these tips for when I am in high school.

Later, when I leave Miss Hagerty’s room with the breakfast tray, I try to imagine myself with a boyfriend. I could be like Zelda Gilroy on Dobie Gillis. Or maybe I should be like Thalia Menninger, since she’s the girl Dobie is always after. And I wouldn’t put him off, like Thalia does. I would be happy to sit with Dobie in the malt shop. He’s a little old for me, but he’s awfully cute. I would wear swirly skirts, and blouses with puffy sleeves, and wide patent leather belts, and I would tease my hair so it puffed out behind a pink elastic headband. At the malt shop, Dobie and I would buy one malt with two straws so we could sip from it together, and everyone who saw us would know we were boyfriend and girlfriend. I only hope that Dobie would do the talking for both of us and it really wouldn’t matter that I’m shy.

As I carry Miss Hagerty’s tray down the hall Mr. Penny comes out of his room wearing wrinkled pants and a wrinkled shirt, and his morning face. I say, “Hi, Mr. Penny,” and keep on going because he absolutely cannot have a conversation until he has a cup of coffee in him.

I take the tray back to the kitchen, and join Mom and Dad, now dressed and fresh looking, in the dining room for breakfast. Mr. Penny will join us later, I know, but Angel Valentine will not. Angel watches her waistline, plus she is ambitious about her secretarial job at the bank, and she says it makes a good impression if she is at her desk in the morning before her boss arrives. So Angel breezes into the dining room dressed like one of those Dobie Gillis girls, gulps down a cup of coffee, and runs out the door calling, “Enjoy your first day of vacation, Hattie.”

I think Angel is absolutely wonderful, and I wish I were her little sister, even though I have known her for only a month.

After breakfast, everybody bustles off. Mr. Penny, who is generally in a hurry, says he must go into town lickety-split, right now, he has errands to do. Miss Hagerty decides to sit on the front porch and knit. Cookie gets busy with lunch. Toby diAngeli shows up to help Mom clean the bedrooms. And Dad goes to work in his third-floor studio.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

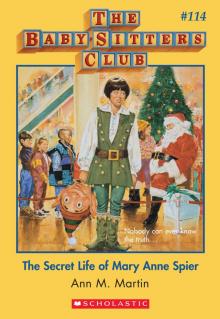

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

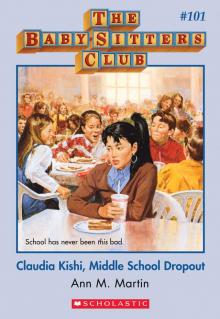

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

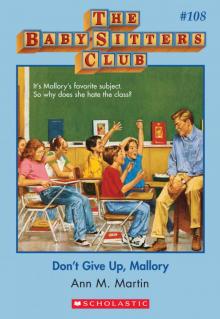

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

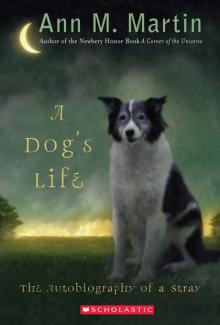

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

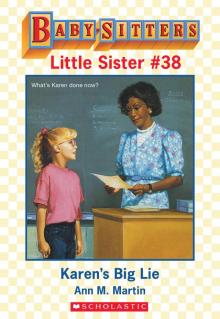

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

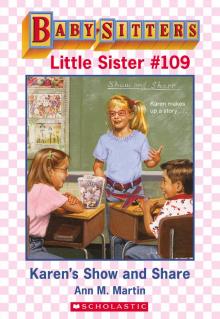

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

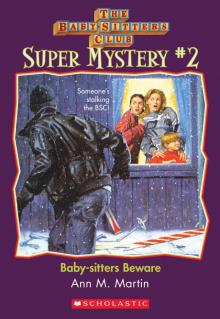

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030