- Home

- Ann M. Martin

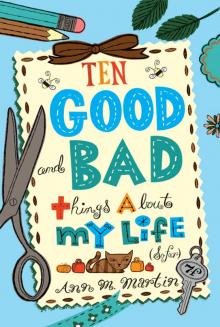

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Page 16

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Read online

Page 16

JBIII looked calm and undisturbed. “One of the keys to our business,” he said, “will be making sure we charge more money for the finished items than we spent buying the supplies. And we’ll only buy what we need to fill our orders, nothing extra.”

This was sounding better and better. “Hey!” I exclaimed. “After you’ve printed out the cards—or the invitations or whatever—I could add special touches to them. You know, like glitter or ribbons or sequins. Of course, we’d have to charge more for those items.” I paused, frowning. “Huh. On the other hand…”

“On what other hand?” asked JBIII, looking slightly annoyed.

“Well, on the other hand, do you think people will really want to buy this stuff? After all, most people just send e-mail now. They don’t write actual thank-you notes or send invitations anymore. They just type a few lines into their computers and click Send.”

“Not everyone,” said JBIII. “Plenty of people like to do things the old-fashioned way. Like my mom, who only reads real books. She says she will never, ever get into bed at the end of a long day with a piece of electronic equipment. She wants pages that she can hold in her hands. She likes turning the pages and imagining who else might have held the book and turned the pages before she did. She says she even likes the way books smell and that nothing will ever take the place of that. And I think lots of people would rather send a nice handmade card or invitation—one with colorful flowers—”

“Decorated with sequins!”

“—that someone could put up on their refrigerator and admire. Anyway,” JBIII continued, “the very first thing we should do is make some samples to show our neighbors. Then we can take orders. If no one orders anything, well, it will be sad, but at least we won’t have wasted any money. I have enough supplies here so that we can make samples.”

So we set to work. JBIII found an old loose-leaf notebook and we replaced the lined paper that was in it with pieces of oaktag.

“We’ll glue our samples on these pages and then we’ll have a professional book to show our neigh—our customers,” said JBIII. “Now, what should we put in the sample book?”

“How about two designs for notecards—maybe one that says ‘Thank You’ on the front—and two designs for invitations and one design for address labels. And the art can be mix-and-match.”

“What do you mean ‘mix-and-match’?”

“Well, if someone likes the art on the address labels but wants it on invitations, we could do that. Any of the designs could go on any of our, um, products.”

“Oh, that’s good!” said JBIII admiringly. “Actually, if we use the designs that way, I can make up more than five samples.”

I got out my markers and paper and by lunchtime our sample book was ready. I had drawn bumblebees and tulips, a mouse holding a piece of cheese in its front paws, and a simple vine of leaves and flowers like this:

And JBIII had used all the designs to make note cards, invitations, and labels. I had also designed a fancy pink-and-green THANK YOU, which he’d made into another notecard. We wanted to start taking orders right then, but we could both hear JBIII’s stomach growling, which we thought might not be good for business, so we made peanut butter sandwiches and ate them in a big hurry before carrying the sample book into JBIII’s living room.

“Mom, Dad,” said my best friend, “you have the honor of being our first customers.” We sat together on the couch, the sample book open across our laps, Mr. and Mrs. Brubaker on either side of us.

“These are lovely!” exclaimed Mrs. Brubaker as she examined our product lines. She said this in a genuine way, not in that way some grown-ups have of sounding all excited when you know that what they really mean is, “How pathetic. And look at all the trouble you went to. I guess I’ll have to buy something out of pity.”

“I’ll say,” agreed Mr. Brubaker, also in a genuine way.

And before we knew it, JBIII and I had taken our first orders—a box of the thank-you notes for Mrs. Brubaker, and a sheet of bee-and-tulip address labels for Mr. Brubaker, but with JBIII’s mother’s address on them.

“I guess we don’t have any designs for men,” JBIII whispered to me, and we decided to get to work on that as soon as we had time.

JBIII wrote down the orders on a notepad and then we closed the sample book and set off.

“Only go to the neighbors you know!” called Mr. Brubaker as JBIII and I stepped into the hall.

Our first stop was at the apartment next door, where a very old man seemed absolutely thrilled to see JBIII and me and ordered some mouse and cheese notecards for his granddaughter. Across the hall an annoyed-looking teenage boy answered the door and I knew right away we weren’t going to make a sale and I was right. But down the hall in the apartment by the elevator a young couple ordered three sheets of address labels, and just as we were about to leave the man suddenly said, “Oh, wait! Emily, we should order invitations for Brielle’s birthday party.” And then the woman said, “The bumblebees are awfully cute.” And I said, “I could hand-decorate them with glitter.” And her eyes grew wide and she asked for twenty special-order invitations.

By the time we had visited people on the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors, we had taken orders for fourteen different items, including three special items that would be hand-decorated.

“This is amazing!” I exclaimed.

“Definitely. Okay. Let’s stop here and go buy supplies.”

“Stop here! Why? Everyone’s ordering stuff. We should keep going.”

“Nope. A good businessperson doesn’t get in over his head,” said JBIII, which was probably something he had heard his father the lamp salesman say from time to time. “We should fill these orders first, just to make sure we can actually do it, and also so we don’t make anyone wait too long for their merchandise. Come on. Let’s go to Steve-Dan’s. How much money do you have?”

I gaped at my friend. “Zero.”

“Oh.”

“How much do you have?”

“Three dollars.”

“How much do you think the supplies will cost?”

JBIII frowned up his face and did some arithmetic in his head while we waited for the elevator. “I’m not sure,” he said finally, “but more than three dollars.”

We went back to JBIII’s apartment, where we found a calculator and figured out how much money we would need at the store, and then how much money we would have after we had filled our orders and gotten paid. If we borrowed some money from his parents we could pay them back quickly and still have a profit for ourselves.

“But remember, after this, we’ll always have to use our earnings to buy supplies,” said JBIII, which is the annoying kind of thing my father the economist would say.

“Yeah, but what’s left over is just for us,” I replied.

Like for investing in an iPod or a hamster.

The Brubakers weren’t too thrilled with the idea of lending their son and me money until JBIII showed them our math. Then Mr. Brubaker drew up a document for us, which I think was his way of saying that even though we were kids he still expected to be paid back promptly. So we signed the paper with our best signatures:

And then JBIII said, “Can we go to the store by ourselves?” and his mother was like, no, and she came with us. BUT … when we reached the store, she said, “You know what? There’s too much air-conditioning in there. I’ll wait for you outside,” and that was her way of giving us a little independence, since we were businesspeople with profits and good math.

In the store I lingered by the display of rubber stamps and then by some hot-glue guns and by a whole lot of other items that weren’t on JBIII’s shopping list, and finally he said, “If you want to buy any of those things you’ll have to pay my parents back with your own portion of the profits,” so then we just put blank notecards and invitations and sheets of labels in our basket and boringly paid for them.

Still, it was exciting when the salesman saw us shopping all by ourselves without an adult and I

was able to say to him, “We’ve gone into business. We promise to buy all our supplies here. Do we get a discount?”

“Not a discount,” he replied, “but a frequent shopper card.” And he punched a little hole in the top of a plasticized card and handed it to us. “When you have ten holes punched in the card,” he said, “you’ll get ten percent off of your next purchase.”

JBIII and I were officially in business.

21

X. JBIII and I went into business.

A. JBIII got an excellent idea.

B. I surprised my parents.

When JBIII and I returned to the Brubakers’ office with our supplies it was late in the afternoon, but we got to work filling our orders anyway. JBIII said that responsible businesspeople wouldn’t waste time and that we should keep our customers happy. I was just eager to start gluing glitter to the bees. Plus, I wanted my money.

By the time Mom phoned to tell me to come home for dinner, JBIII had printed out three sets of notecards and packaged them in tissue paper tied with ribbon, and I was nearly done with the glittery bumblebees. The cards were drying on every surface in the office, and if you must know the truth, I had sneezed and blown yellow glitter across the carpet, which JBIII said we would have to clean up before his parents saw it. And also that we should use newspapers the next time we got a glitter order. But we were happy with our progress and couldn’t wait to get back to work the next morning.

On Sunday, without being asked, I showed up at the Brubakers’ at 8:00 a.m. in the morning, which may have been a little early, because Mr. Brubaker was still in his pajamas, and he ran into the bedroom when he saw me. But JBIII and I were all businesslike and I didn’t pay any attention to his father’s GOT MILK? T-shirt with the giant rip in the underarm.

We just set to work, and an hour later JBIII announced, “Okay. All the seventh-floor orders have been filled. Let’s deliver them.”

“Shouldn’t we finish the rest of the orders first?” I asked. I was busily attaching pink ribbons to a special set of thank-you notes for a lady on the ninth floor.

“If we deliver these, we’ll get paid for them,” JBIII pointed out, but we decided to wait since it was only 9:00 and we didn’t want to embarrass/annoy/wake up any of our clients.

Sunday turned out to be quite a day for us. Here’s what we’d done by dinnertime:

1. Filled all the orders we had taken the day before.

2. Delivered the orders and gotten paid for them.

3. Reimbursed (which is a fancy economics word meaning “paid back”) the Brubakers for their loan. (I made them tear up the contract since I didn’t want a piece of paper hanging around that said JBIII and I owed anybody $$.)

4. Taken orders on floors 2–4 of JBIII’s building.

5. Bought supplies for the new orders and paid for them out of our profits from the first orders. IMPORTANT NOTE: I still had some $$ left over, and I had a brand-new idea for what to do with all the cash I’d be earning.

6. Started filling the new orders.

“And just think,” said JBIII happily as he set to work printing out a sheet of mouse-and-cheese address labels, “when we get paid for these orders, we’ll make even more money than before because we won’t have to pay my parents back for anything.”

* * *

The next week was very exciting. JBIII and I took orders every morning and spent the afternoons filling them. When we ran out of people in JBIII’s building we went door-to-door in my building.

“And when we’re done with my building we can show our products to our parents’ friends,” I said. “Oh! Oh! And we could go to The Towers and show the sample book to Daddy Bo’s friends.”

“My dad could take the book to his store,” suggested JBIII.

We were going to be millionaires.

JBIII and I were careful with our money. We never bought more supplies than we needed and we always bought the supplies as soon as we’d gotten paid, so we didn’t have to borrow any more $$. And one day we even gave $10 to the Brubakers since we were using their computer equipment so much. And they accepted it, instead of saying, like, “Oh, no, children, you hang on to this,” because they knew we were running a professional outfit.

I was very busy. And happy. It was hard to believe that not long ago I’d been dragging pathetically around the house with nothing to do except make a necklace for Bitey and sing mean songs about Lexie. Now I saw JBIII every day. We took orders and filled them, and in my spare time I thought up new designs. Our sample book was growing. I wasn’t rich exactly, but my wallet was getting fatter. And the days were flying by.

Which is why I was surprised when one afternoon as JBIII and I were working in his room (his mother needed the computer so we had temporarily moved our operations out of the office), my best friend said, “I can’t believe the summer is over.”

“It isn’t over,” I said automatically.

“Well, I know it isn’t technically over. That won’t happen until the end of September. But school starts in six days.”

“WHAT?” I was working on a special-order card—gluing white pom-poms onto bunnies where their tails should be—and I stopped with my hands in midair.

“Yup,” said JBIII. “Six days.”

“But that’s impossible.” Hadn’t I just been sitting in Mr. Potter’s room, lying to my friends about my nonexistent trip to the Wild West?

“Nope. It really is six days.”

Then it was time to carry out the idea I’d had.

That night Mom and Dad and Lexie and I ate dinner in the family room as usual. Since I was now a businessperson, earning $$ and being responsible (finally) and mature (sort of), I cleared a space for myself at Dad’s desk and ate my tuna-noodle casserole without spilling a bit. Every now and then, particularly when I reached for my glass of milk, one of my family members would look at me nervously, but the meal was uneventful.

I waited until we had all finished eating and then I cleared the table. Dad stood up to help me, but I said, “No, you stay there. Let me do this. I promise I won’t drop anything.”

And I didn’t.

This was surprising enough, but I had another surprise in store for my family. When I returned to the table I reached into my pocket, pulled out a wad of bills, and set it on the table. The wad was so fat that when I’d tried to stuff all the $$ into my wallet a little earlier, the wallet wouldn’t close.

Lexie looked at the bills and raised her eyebrows. “Where did that come from?”

“From P&J Designs,” I replied, which that is what JBIII and I had named our business.

“You earned all that?” asked my sister.

“Well, more really, since JBThree and I have to buy our supplies with our earnings. And also, I wanted a yo-yo. But this is what’s left over.”

“Pearl, I am so proud of you!” exclaimed my mother.

“You and JB had a good idea and you carried it out very professionally,” added Dad.

“Well, actually, JBThree had the original idea,” I said modestly.

“But you have the artistic talent,” said Mom. “And you really are treating your idea professionally.”

Mom and Dad had each ordered something from P&J Designs, and they had received the finished products in a timely fashion, which had impressed them.

“Are you still getting orders?” asked Lexie, eyeing my wad again.

“Yup. Every day. We take orders in the morning and fill them in the afternoon. I guess we’ll have to slow down when school starts, though. Speaking of which,” I continued, “are we going to BuyMore-PayLess for back-to-school shopping on Saturday?”

We went there so often now that we had each been given a free green canvas SHOP HAPPY AT BUYMORE-PAYLESS! bag. We left the bags hanging on the knob of our front door so we wouldn’t forget to take them with us every time we headed for the subway to Brooklyn.

Mom nodded. “I think we’d better. Saturday will be our only chance before school begins.”

“Go

od,” I said. I pushed the $$ farther across the table toward my parents. “That’s for the trip.”

“What?” said Mom and Dad.

“You’re kidding, right?” said Lexie, and I couldn’t tell whether she was surprised or jealous.

“I don’t know if it will pay for everything I need,” I went on, “because I kind of grew out of a lot of my clothes over the summer, but I want to pay for as much as I can.”

“All your earnings? Are you sure?” said Mom, and tears filled her eyes, which is not a normal thing, in that I mostly make her cry by dropping eggs out of the window or forgetting to hand in my homework for an entire week.

“I’m sure,” I said. And I was. There was just one sad thing about the success of P&J Designs, which was that now Dad was the only Littlefield without a job of his own. His wife was employed and his daughters were employed and Dad was sort of earning some $$ here and there, but it just wasn’t the same as when he was the important economics professor, a job he loved and wanted back.

* * *

Two days later Mom and Dad and Lexie and I walked through the entrance of BuyMore-PayLess, each with a SHOP HAPPY bag slung over one shoulder. Mom was holding a list that was almost as long as the one she’d consulted while packing me up for my overnight week at Camp Merrimac. She glanced at it, then said, “Okay, grab two shopping carts. The list is long and the morning is short.” (Sometimes I can sort of see why my mother became a writer.) She tore the list in half and handed the bottom part to my father. “We’ll split up. You and Lexie go together, and I’ll go with Pearl, since she might need some help trying on clothes.” (Which I didn’t, since I was ten, for heaven’s sake, but whatever.)

“Now,” Mom went on, looking around the store, which is approx. the size of an airport, “school supplies are over there, winter coats are over there, and girls’ clothes are over there. We don’t need any food, so we can avoid the grocery aisles. All right. Let’s get going.”

I looked at our half of the list as Dad and Lexie trundled away. I certainly did need a lot of things—notebooks, a new backpack, an assignment pad, a calculator, socks, underwear, sneakers, a winter jacket, jeans, a fleece top … I guess this is what happens when you enter fifth grade and also have a growth spurt.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

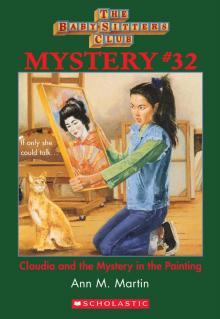

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

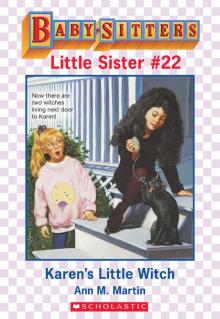

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030