- Home

- Ann M. Martin

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Page 2

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Read online

Page 2

On to the next memory picture: my sister, best friend, and fellow BSC member, Mary Anne. She was sitting on the end of Claudia’s bed, next to Stacey. I saw her laugh at something Kristy had just said, and her whole face lit up. Snap! That’s when I took my picture. Not that I really need one of Mary Anne. We’re so close that she’s always in my heart.

Mary Anne, by the way, is the club’s secretary, and she does an awesome job. She keeps track of all our schedules and could tell you immediately which of us would be free for a sitting job from two-thirty until five a week from next Thursday.

In fact, Mary Anne swung into action as I was watching her, when Kristy answered a call from a new client, a Mrs. Cornell. She needed a sitter that Saturday afternoon for her two children, and she told Kristy she lived at 159 Green House Drive, which is in Kristy’s neighborhood. She called the place “Livingston House.”

Mary Anne found that Kristy and I were the only club members available, and Kristy said she had plans for that day, so Mary Anne signed me up for the job and Kristy called Mrs. Cornell back. That’s the BSC in action. Simple, no?

These days my official position in the BSC is as an honorary member. I used to be the alternate officer, though, which meant that I would cover for any other member who couldn’t make it to a meeting. That office is now held by the newest member of the BSC, Abby Stevenson. She and her twin sister, Anna, moved to Stoneybrook after I moved away, so I don’t know either of them too well. I do know that they came here from Long Island with their mom, and that their dad died in a car wreck when they were nine. Anna’s not in the BSC; she’s way too busy with her music. I hear she’s awesome on the violin.

My memory picture of Abby would show a laughing girl with deep brown eyes and long, curly, thick, dark hair. Abby’s full of fun, but I sometimes see a sadness in her eyes. I guess it’s because she misses her dad.

Abby doesn’t talk about him much. Instead, she talks about everything else — at a mile a minute. She’s always cracking jokes, lots of which are at her own expense. For example, she likes to make fun of her allergies and asthma, which are actually serious business (she had to go to the emergency room for an asthma attack not long ago). She doesn’t like to take her health problems too seriously, though, and she definitely doesn’t like to let them slow her down. She’s great at sports; Kristy says she’s a natural athlete.

Abby and her sister recently turned thirteen, which makes them the same age as most of the rest of us in the BSC. The only younger members are Jessi Ramsey and Mallory Pike, who are both eleven. They’re our junior officers, which means they mostly take afternoon jobs. They’re not allowed to baby-sit at night except for their own families.

My memory picture of Jessi would show a slim African American girl with dark hair and eyes and long, strong arms and legs. Jessi’s a very advanced ballet student, and it shows in her elegant bearing. But she’s also a regular girl, one who loves to read horse books and giggle and tell secrets to her best friend, who happens to be Mallory.

I guess my memory picture would probably show the two of them together, since they’re rarely apart. That day, for example, they were sprawled on Claudia’s rug together. So, next to Jessi my picture would show a girl with curly chestnut hair and blue eyes framed by glasses. Mal has a great sense of humor, but she often looks serious. Maybe it’s because she’s thinking about her writing. Mal loves to write, but it’s hard for her to find a quiet moment for it; she has seven younger brothers and sisters! (Jessi, on the other hand, has only two: a younger sister and a baby brother.)

There are two other members of the BSC, Shannon Kilbourne and Logan Bruno (Mary Anne’s boyfriend), but neither of them was in Claudia’s room that day. They’re associate members, which means that while they don’t come to meetings regularly, they are on call if we need extra help. My memory picture of Shannon would show a blonde girl with high cheekbones, and the picture would probably be blurred, because Shannon’s always on the run. She keeps very busy with clubs and other after-school activities; even during the summer she’s usually pretty booked up. Logan’s picture would show an athletic, funny guy — and naturally he’d be holding Mary Anne’s hand.

As you can see, my memory album is well filled. I’ll carry those memory pictures of my BSC friends with me when I go back to California, and I have the feeling they’ll be carrying memory pictures of me, too.

Oh, one last thing about the meeting that day. A sort of weird thing. We received another call toward the end of the meeting, from a Mrs. Keats. She was looking for a sitter for her three kids for Saturday afternoon — and she gave us the same address that Mrs. Cornell had given us! At first we were confused. Were two members of the same family calling by mistake? Or did they really need two sitters for simultaneous jobs at the same house? Since Mrs. Keats said she had three kids and Mrs. Cornell had mentioned two, we figured there were two different groups of kids, so in the end Kristy took the second job, giving up her plans for the day. I was glad; having her there would make the job even more fun. Suddenly, I couldn’t wait to meet our new clients.

I looked over at Kristy, and she looked back at me. She raised her right eyebrow about an eighth of an inch.

I know Kristy very well, well enough to translate her eyebrow-raises. That one meant, “This is majorly weird.” I gave her the tiniest nod, to show I agreed.

The two of us were seated in a pair of humongous, overstuffed armchairs, which faced each other across a room full of other humongous, overstuffed furniture. We were in Livingston House, waiting to meet our newest clients.

We’d arrived on time (of course), and as we stood on the wide marble front steps I felt a little nervous. I wondered if Kristy did, too. She’s used to living in a fancy neighborhood, but Livingston House is quite a few steps above Watson Brewer’s place. I mean, this place looks like a certain large white house we’ve all seen pictures of. You know, the one at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, in Washington D.C.? Well, Livingston House may not be the home of presidents, but it sure is impressive. It’s this enormous white structure, with pillars and two-story-high windows all along the front. The grounds — you can’t call that much land a yard — are awesome, too. Rolling green lawns, flower beds bursting with blooms, perfectly manicured shrubs — the whole bit. There are statues everywhere, and I saw two fountains spouting water. Kristy told me she’d heard about an Olympic-sized pool out back, with a pool house bigger than most people’s regular houses.

Anyway, we knocked on the oversized red door, using the brass knocker, which was shaped like the head of a lion. I heard footsteps approaching from inside, and I wondered whether Mrs. Cornell or Mrs. Keats would answer the door.

Neither one did.

Instead, the door swung open to reveal a really cute older guy with dark hair, dark eyes, and a neatly trimmed dark beard and mustache.

He looked at Kristy, then at me, and raised his eyebrows. “Yes?” he said.

“We’re — uh —” I began. Somehow the words wouldn’t come out right.

Kristy tried next. “Is Mrs. — um, Mrs. —” Obviously, the guy’s dark gaze was affecting her as well, which was unusual for Kristy. She couldn’t even remember her client’s name!

Just then, the guy finally cracked a smile. “You must be the baby-sitters,” he said, nodding at the decorated Kid-Kit we each carried. (I had a feeling he’d known that all along, and was just giving us a hard time.) “Come on in.”

He stepped back from the door and motioned us into the foyer, which was about as big as the living room of my Stoneybrook house.

“Some front hall,” Kristy muttered under her breath. I noticed her looking around, taking in the black-and-white-tiled floor, the fancy red and gold chairs against the wall, the immense brass coatrack.

“This way, please,” said the dark-haired man. He led us through one of the many doorways leading off the hall and ushered us into the room with the humongous furniture. There was a fireplace, too, lots of oriental rugs, and a bunch of spindl

y but very expensive-looking little tables.

Hanging above the fireplace was a huge portrait in a fancy gold frame. A nameplate on the bottom of the frame identified the person pictured as Arthur Livingston. It was a good thing the picture had a caption. It was the ugliest painting I’d ever seen, and if I hadn’t been able to read that it was a picture of a man I might never have figured it out. He looked like a cross between George Washington, Whistler’s Mother, and the Elephant Man. The colors were awful, the background was a mess of blurry brush strokes, and the artist clearly hadn’t known very much about how to paint noses. Or hands. Or mouths. I looked at the painting, fascinated with its repulsiveness. Kristy was staring at it, too.

“It is rather ugly, isn’t it?” observed the man who had let us in. “There are dozens of portraits of Mr. Livingston around the house. He had one painted every year of his married life.” He looked at the painting again and grimaced. “This is probably the worst of them all,” he said, shaking his head. “Now, where are Mrs. Cornell and Mrs. Keats?”

Just what I’d been wondering.

As if on cue, we heard footsteps in the hall and then the door to the room swung open and two women — both around my mom’s age — entered the room. They were tall, with reddish-brown hair and clear blue eyes. Though they had come in together, there seemed to be some almost-physical force keeping them at arm’s length. Each seemed alone because of the way they barely acknowledged each other.

“Ah, you must be Dawn,” said one, at the same time that the other one said, “Welcome, girls. Which one of you is Kristy?”

They stopped and glared at each other, each waiting for the other to start speaking again.

As Kristy said later, it would have been funny if it hadn’t been so awkward.

Neither of us knew what to do, so we just stood there. Finally, one of the women — the one who had mentioned my name — said, “I’m Mrs. Cornell. And this is Mrs. Keats.” She gestured vaguely toward the other woman. “And I see you’ve already met Mr. Irving, our butler.”

Butler? I saw Kristy’s eyebrow twitch, and I knew exactly what she was thinking. I was thinking the same thing. How could such a young guy be a butler?

“Please, call me John,” said Mr. Irving with a smile.

Mrs. Cornell shot him a cold glance. She didn’t seem to appreciate his friendliness.

Hoping to head off any unpleasantness, I jumped right in. “I’m Dawn Schafer,” I said, “and this is Kristy Thomas.”

“Baby-sitters Club, at your service,” added Kristy, grinning.

Neither of the two women returned her smile, but both of them nodded to us.

Then Mrs. Keats spoke up. “My sister and I are here in Stoneybrook to straighten up our late father’s estate.” She looked up at the portrait of Arthur Livingston. “He passed away about a year ago.”

Kristy and I glanced at each other. So, the two women were sisters. That made the kids we were going to sit for cousins.

“Our husbands are home, working, so while we’re here,” Mrs. Keats continued, “we are going to need qualified, responsible baby-sitters for our children. I must say that your club came highly recommended.” She sniffed. “I hope you’ll live up to your advance billing.”

I had the feeling she doubted that we would. Nothing like being judged before you even begin a job.

“In any case,” she concluded, “we would appreciate it if you would keep our children apart while you are sitting. It will make things easier for all parties involved.” She gave another sniff — one that sounded slightly accusing, to my mind.

“Don’t the children like to play together?” I asked, without stopping to think. After all, they were cousins. You’d think they’d be friendly.

“I think you’ll find they prefer it this way,” said Mrs. Cornell, who was glaring at her sister. “Some of the children are prone to arguing at times.”

“Only if they’re provoked!” snapped Mrs. Keats.

“Well,” said Kristy, stepping forward. “We’d love to meet our new charges.” I could tell she was trying to head off an argument.

Both women stepped back a little, and nodded. “Of course,” said Mrs. Keats. “Why don’t you come with me, Kristy?”

“And you can come with me,” Mrs. Cornell said to me.

Kristy and I exchanged one more glance, and that was the last I saw of her until our job was over and we met downstairs in the foyer.

Later, she told me everything that had happened.

Apparently, the sisters had divided the house into two parts for the duration of their stay. It wasn’t hard to do, since the place was so enormous. Basically, the wing to the left of the front door belonged to the Keats family, while the wing to the right was where the Cornells were camped out.

Mrs. Keats led Kristy up a wide staircase, down a hall, and up another staircase. On the way up the second set of stairs, they passed a woman who looked a lot like Mrs. Keats and Mrs. Cornell, only younger. The two women nodded to each other, but didn’t stop to talk. When Kristy and Mrs. Keats reached the top of the stairs, Mrs. Keats explained that the woman on the stairs was their younger sister, Amy, who had been living with their father until just before he died. (Kristy didn’t see Amy again for the rest of the day. Neither she nor John, the butler, seemed to have any part in the care of the children.)

Mrs. Keats then showed Kristy into a large, sunny playroom, and introduced her to the kids: Eliza, nine, Hallie, seven, and Jeremy, the youngest, five. They all had their mother’s reddish hair and blue eyes.

Kristy reported that the kids seemed normal, despite all the weirdness in the house. They were playing Pogs when she showed up, and they invited her to join in. As soon as Mrs. Keats left the room, they began to bombard Kristy with questions about their cousins.

“Did you see them?” demanded Eliza.

“What are they like?” asked Hallie.

“Are they mean?” asked Jeremy, a little timidly.

“No, of course not,” said Kristy, even though she hadn’t met the Cornell children. “They’re just like you.”

“Then why did we fight with them?” asked Eliza. “Mom says that the last time we were together, we had a huge fight. I barely remember it. I can hardly remember my cousins at all, except for maybe Katharine. She’s the older one.”

Kristy had a feeling that if there had been a fight, it had been fueled by the feuding sisters. Otherwise, wouldn’t the cousins remember what they’d fought about?

Since she couldn’t answer any more questions about the Cornell kids, Kristy diverted the three Keats children by showing them the contents of her Kid-Kit, and the afternoon passed with no further incidents. But Kristy couldn’t help thinking, as she watched the three kids playing happily together, how great it would be to introduce all the Livingston grandchildren to each other — with no angry adults around.

I was thinking the same thing, over in the Cornell wing. I’d met Katharine, who at nine was the same age as Eliza, and Tilly, who was six. Both of them had what Kristy and I were realizing was the “Livingston look”: tall, with reddish hair and blue eyes. They were great kids, and they wanted to know all about their cousins.

When Kristy and I talked about it later, we tried to figure out some way to bring the cousins together. Kristy even considered suspending the BSC rule about having two sitters for more than four children. If the BSC sent only one sitter to Livingston House, the kids would have to play together, whether the sisters liked it or not. But, as Kristy pointed out, that rule is there for a reason. It’s really not safe for one sitter to watch five kids. Still, there had to be a way. It just didn’t seem right to deny the kids the fun of playing together because their mothers couldn’t act like a family.

Normally, I become very bored very quickly when adults stand around talking and talking and talking in that endless, monotonous way that only adults can manage.

But listening to my stepfather Richard’s conversation with Lyn Iorio was a different matter. I didn

’t tune out. I didn’t roll my eyes up to the sky. I didn’t stand there wishing I had my Walkman. Instead, I listened to every word. Why? Well, because they were talking about a topic that interested me — a lot. They were talking about the strange happenings at Livingston House.

It was that same Saturday, and Kristy and I had just said good-bye to our new clients. Kristy had run home for dinner, and I headed for Richard’s car, which was parked across the street from the long driveway leading to Livingston House. He had come to pick me up, and, as always, he was on time. As I neared the car, I saw that he was leaning against it, talking to a woman with a perfect blonde pageboy hairdo. She was dressed in sweats and running shoes, and it looked as if she’d just finished jogging. She was sipping from one of those plastic water bottles, and her face was pink.

Richard looked up and saw me approaching. “Ah, there she is,” he said, smiling at me. “Lyn, this is Dawn. Dawn, this is Lyn Iorio. She’s a neighbor of your clients.”

“Nice to meet you, Dawn,” said Ms. Iorio, sticking out her hand.

I shook it. “Nice to meet you, too.”

“Lyn is a lawyer,” said Richard. “A very good one, too. We’ve worked together many times over the years. Right now she happens to be working for the same people you are.”

I wasn’t sure what he meant. “You’re working for Mrs. Cornell?” I asked.

“Sort of,” she answered with a smile. “Actually, I’m working for her father, even though he has passed away. I’m the executor of his estate, which means I have to make sure that his will is carried out exactly as he wanted it to be.”

“You knew him quite well, didn’t you?” Richard asked her.

“I was close friends with Mrs. Livingston,” she replied. “I think Arthur liked knowing that I had a personal connection to his family.”

“So you know Mrs. Keats and Mrs. Cornell?” I asked. “And Amy Livingston?”

“Sure,” said Ms. Iorio. “I’ve known them since they were little girls. They never did have a great relationship, even then.” She lowered her voice. “And from what I hear,” she added, “the squabbles they used to have as children are nothing compared to the fights they’re having now.”

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

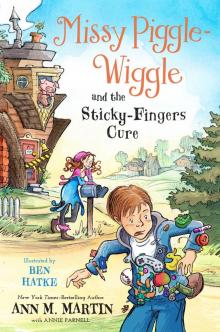

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030