- Home

- Ann M. Martin

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Page 2

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Read online

Page 2

Stacey’s a diabetic, which I think gives her a certain perspective on life. That is, she doesn’t take it for granted. Diabetes is a serious, lifelong disease. Stacey’s body doesn’t process sugars correctly, which means that she has to be very, very careful about what she eats, and must give herself shots of insulin, which her body needs but doesn’t produce.

We all paid our dues, and just as Stacey was closing the envelope, the phone rang. Kristy grabbed it. “Hello, Baby-sitters Club,” she said. She listened for a few minutes, making little “mmm-hmm” noises, and then hung up, after promising she’d call right back.

“That was a new client,” she explained with a smile. Kristy loves new clients. Hearing from them proves, according to her, that the BSC receives great word-of-mouth advertising from our regular clients. We used to advertise a lot, with fliers, but we find we don’t need to much anymore. “Her name’s Mrs. Martinez,” Kristy continued. “She teaches science at the high school, and so does her husband. They’re in a bind because their regular sitter just quit, and they need someone to watch their kids every afternoon — starting tomorrow — until they can find a new one.” Kristy turned to me. “Is there any way we can take on a commitment like that?” she asked.

I pulled the record book onto my lap and opened it. I’m the club secretary, and I pride myself on my neat, accurate record-keeping. I can see at a glance which of us is available for any particular job, and let me tell you, keeping track of all our schedules is not easy. “Hmmm, doesn’t look good,” I said. “Nobody has every single afternoon free. But if we each take a few afternoons here and there, we could do it. I can take the first shift tomorrow.”

“I’m sure Mrs. Martinez wouldn’t mind, as long as the hours are covered,” said Kristy, reaching for the phone. She talked to Mrs. Martinez for a few minutes, then hung up, looking surprised. “She says that’ll be fine,” she informed us. “But listen to what else she told me. Mrs. Martinez says that their house is a bit of a mess. They just had a small fire, and she says things are still a little smoky and smelly. Guess where they live.”

I knew right away. “Near Miller’s Park?” I asked. Kristy nodded. “Theirs must be the house that the paper mentioned this morning. The one that Fowler needs to buy in order to develop Miller’s Park!”

“Isn’t that the most amazing coincidence?” Kristy marveled. “Here we were, just talking about what’s happening over there, and she calls.”

“I may have to put off sitting for the Martinezes until they have things cleaned up,” said Abby. “That smoke might make my allergies kick into high gear.”

Abby Stevenson is the newest member of the BSC. She was invited to join after Dawn moved back to California, and she’s taken over Dawn’s position in the club, which is alternate officer. That just means she fills in for any of the other officers who might be absent from a meeting.

While Abby has taken Dawn’s position, she can never exactly take her place. I like Abby a lot — we all do — but she and Dawn are very different. Abby just moved here from Long Island, which is about as much on the East Coast as you can be, while Dawn will always love California. And Abby is full of energy and rushes into things, while Dawn is more laid-back.

Abby is an identical twin. Her sister’s name is Anna. I don’t know Anna too well yet, but I do know that she’s an amazing musician. She plays violin on practically a professional level. Abby, meanwhile, loves sports and almost any kind of physical activity. She runs, she plays soccer, she skis. And she does it all despite the fact that she’s allergic to just about everything. As if that weren’t enough, she also has asthma.

Abby and Anna live in Kristy’s neighborhood with their mom, who commutes to work in New York City. Their dad died in a car wreck a few years ago. Abby never talks about that, but I can tell that his death affected her in some really major ways. Maybe it’s just that I can identify with her, since I’m what I call a “half-orphan,” too.

Since no other phone calls came in for a few minutes, we started to talk about the new clients. “How old are the kids?” asked Mallory. Kristy told her the Martinezes have an eight-year-old boy and a three-year-old girl. “Maybe Nicky knows the boy from school,” said Mal.

Mallory Pike and her best friend Jessica Ramsey are the club’s junior officers, which means that since they’re eleven and in the sixth grade (unlike the rest of us, who are all thirteen and in the eighth grade), they aren’t allowed to sit at night unless it’s for their own families. They take care of a lot of our afternoon jobs.

It was a good bet that Mal would have a sister or brother to match the new kids’ ages. She has seven younger siblings, including a set of identical triplets. If you ask her, she can say all of their names in one breath, like this: “ByronAdamJordanVanessaNickyMargoClaire!” The Pike kids are a handful, no doubt about it. Mal has had a lot of sitting experience for someone her age.

Mal is white, with reddish-brown hair, glasses, and braces. She’s cute now, and she’s going to be really pretty someday, but she doesn’t believe that. She’s smart, too, and a good artist and writer. When she grows up she wants to be an author and illustrator of children’s books.

Jessi has a smaller family. She lives with her parents, her little sister Becca, her baby brother Squirt (real name: John Philip Ramsey, Jr.), and her Aunt Cecelia. Jessi is African American, and has cocoa-brown skin, deep velvety brown eyes, and legs that seem to go on forever. She’s a serious ballet student and an incredible dancer.

There are two more members of the BSC, but neither of them said anything that afternoon, for the very simple reason that neither of them was at the meeting. They’re both associate members, which means that they help out when we have more jobs than we can handle. One of them happens to be Logan. The other is Shannon Kilbourne, who lives in Kristy’s and Abby’s neighborhood but who goes to a private school called Stoneybrook Day School. She’s super-smart, pretty, and fun to be around.

Our meeting wound up soon after Mrs. Martinez’s call. I was excited about having new clients, especially because I would be the first to sit for them. And I was glad they lived near Miller’s Park, if only because I wanted to spend some time there before Fowler destroyed it. I knew that might happen, even if the BSC did everything we could to stop him. We’re the best baby-sitters in Stoneybrook, but I had to admit that wouldn’t mean anything when it came to fighting Reginald Fowler.

“I know, the odor is awful. We’ve had the windows open forever, but it still smells.” Mrs. Martinez was showing me where the fire had started, in the garage, and she’d noticed me wrinkling my nose at the acrid smell of smoke that hung in the air.

It was Tuesday afternoon, and I had just met Mrs. Martinez and her two children: Luke, the eight-year-old, and Amalia, who is three. All three of them had dark hair, dark eyes, and infectious smiles. I liked them already. Their house was small and cozy, and fortunately had not been severely damaged in the fire. The garage was going to need a lot of work, and they’d lost practically everything that had been stored there, but it was the only place where you could see the effects of the fire. The smell, on the other hand, pervaded the entire house.

“How did the fire start?” I asked Mrs. Martinez as we headed back into the house.

I could hear snatches of the “Circle of Life” song as we sat in the kitchen, talking. Mrs. Martinez had brought home a Lion King sing-along video and was letting the kids watch it so that she and I would be able to talk uninterrupted. “This being the first time you’re here, and all,” she’d explained. I was glad she wasn’t the type to run off after a hurried hello. I think it’s important to take the time to talk with new clients and learn a little about their kids, their schedules, and what kind of household rules the family has. Mrs. Martinez seemed to feel the same way. She’d arranged to stay home for a half hour after I’d arrived.

“We still don’t know how the fire started,” she answered. “All we know is that it began in the garage. Fortunately, our baby-sitter at the time

smelled the smoke and was able to move the kids out of the house. Luke ran across the street and told the neighbors, who called the fire department. They showed up quickly. The garage door was open, so they charged in and put the fire out before it could spread into the house.”

“That’s great,” I said.

“It sure is. We were so lucky,” said Mrs. Martinez. She sighed. “It’s going to be a while before we have things back in order, though. My husband and I are both so busy. We run an after-school tutoring program at the high school, and we both teach adult education classes in the evenings. That’s why we need a sitter every day. We’re so glad your club could fill in; we thought we were done for when our other sitter told us she had to quit.”

“Well, I’m glad we could help,” I said. “Personally, I love this neighborhood. Miller’s Park is so pretty! I’ll be glad to sit for you whenever I can.”

“We love Miller’s Park, too,” said Mrs. Martinez. “And Ambrose’s Sawmill. I’d hate to see it destroyed.”

I nodded. “So you won’t sell out to Fowler?” I asked.

“Never!” she replied. “We’ve worked too hard for this house. We would never give it up and start all over again.” She shook her head. “I can’t stand the arrogance of that rich developer. He thinks he can just waltz in here and do anything he likes to Stoneybrook. Well, he’ll find out just how wrong he is. Not everybody can be bought.”

She sounded angry, and I didn’t blame her. After all, who was Fowler? Some guy who thought he could make a lot of money by ruining our town. I was glad to know that the Martinezes were going to stand up to him.

Mrs. Martinez showed me around the kitchen, and pointed out a list of emergency phone numbers she’d posted on a bulletin board by the phone. Then she said good-bye to the kids, gave me a few last-minute instructions on afternoon snacks, and headed off.

“Hey, Luke. Hey, Amalia,” I said, joining them in the living room as their video ended. “What would you guys like to do now?” It was time to become acquainted with my new charges.

“Polly Pocket?” Amalia asked hopefully, holding up a tiny doll. She had crawled onto my lap the second I sat down. I smiled at her. She was very affectionate.

Luke rolled his eyes. “No way am I playing with that dumb doll,” he protested, more to Amalia than to me. So far he hadn’t met my eyes once or talked directly to me. I figured he was shy, which I could relate to. I decided to give him space and hope he’d eventually become more friendly.

“Tell you what,” I said. “How about if we have a quick snack, and then go outside and explore Miller’s Park for a while?”

Amalia agreed happily, once I’d said it was fine with me if she brought Polly Pocket. Luke didn’t seem as enthusiastic, but he said that if I was going, he’d go.

I told them I was going to put together their snack, and that I’d be right back. Amalia curled up in the corner of the couch, crooning to her doll. But Luke followed me into the kitchen. I smiled to myself. Maybe he was already losing his shyness. “Want to pour out some juice for everybody?” I asked him.

“Okay,” he mumbled, looking down at his sneakers. He still wasn’t acting too friendly, but he did seem to want to stay close by me. I was a little confused by his behavior, but I tried not to let it bother me. Every kid is different, and as an experienced sitter I’ve learned to accept those differences and enjoy them.

I wondered what it would take to reach him, to make friends with him. I decided to try flattery. “I hear you were really brave, the way you ran across the street for help on the day of the fire,” I said as I spread cream cheese onto a bagel for Amalia.

“How did you know about that?” he asked, sounding angry. He was looking directly at me for the first time.

“Um, your mom told me,” I answered.

“Yeah? What else did she say?”

“Just that you all were able to leave the house safely,” I replied lamely. Something about Luke’s attitude didn’t seem quite right. Why was he so defensive about the fire? “That must have been a scary day,” I continued, trying to sound neutral.

“It was no big deal,” he said, staring at his sneakers again.

“Were you the first one to smell smoke, or was it your baby-sitter?” I asked, more to keep him talking than because I was interested.

“I don’t know,” he answered quickly. “I really don’t remember much about that day, okay?” He returned the juice carton to the refrigerator and closed the door — hard.

“Okay,” I said. It sounded as if Luke knew — and remembered — more than he was letting on. But if he didn’t want to talk about it, I wasn’t about to force him. After all, I wanted to make friends with him, and I hoped we could both enjoy the time we’d be spending together. I didn’t want him to feel angry at me, or on the spot. “Would you go tell Amalia that the snack is ready?” I asked.

“You come, too,” he insisted.

What was going on here? Luke didn’t want to let me out of his sight, that was obvious. But why? I knew it wasn’t because I had suddenly become his favorite person in the world. I wondered if the fire had been so traumatic that he was now afraid to be alone. Or maybe he’d always been that way. In any case, I decided not to make waves. “Okay,” I agreed. “We’ll both go tell her.”

Half an hour later, when we’d finished eating and cleaning up, the three of us headed outside. It was a warm spring afternoon, and everywhere we looked we saw trees budding, daffodils blooming, and birds singing. The sun was so warm that I took off my sweatshirt and tied it around my waist. Amalia ran ahead, picking dandelions and carrying them back to me. Luke dawdled, staying close behind me and ignoring most of my comments.

Miller’s Park is a beautiful, peaceful place. There’s all sorts of history attached to it, too, but I can never remember the details. All I know is that there’s a stream running through the grounds, and that at this time of year purple violets bloomed beneath the weeping willows. We saw a robin bringing a worm to its nest, and a squirrel digging for nuts, and a duck swimming around on the millpond, acting as if it owned the place.

We poked around Ambrose’s Sawmill, and I read out loud from the sign posted in front of it telling about the planned renovations. The Historical Society had big plans for the site. I felt angry all over again when I thought about Reginald Fowler knocking the place down. Not to mention bulldozing the whole park. I mean, where would the robins and squirrels and ducks go? Didn’t he care?

I kept most of my feelings to myself, though. Amalia wouldn’t have understood anyway, and I didn’t want to be negative around Luke. I was still hoping he’d open up a little more. He did seem to enjoy our walk in the park, but while he never strayed far from my side, he didn’t talk much, either.

The same was true when we found ourselves back at the house.

On the way inside, Luke had opened the mailbox and retrieved the day’s mail. He stood in the hall leafing through it while I helped Amalia out of her jacket. At one point, he glanced up to see if I was watching, and I looked away quickly. But I turned back in time to see him pull a sheet of paper out of an envelope, read it quickly, then tear it into pieces and throw the scraps into a trash basket beneath the hall table.

Now I was really curious.

But it took the rest of the afternoon before I could satisfy my curiosity, because Luke never left my side. Finally, when he went to the bathroom at one point, I made a dash for the trash basket, grabbed the pieces of paper, and tucked them into my pocket.

Later that night, when I returned home, I pulled them out. Unfortunately, I hadn’t been able to grab all the pieces. I could see that there was printing on the note, in large, dark capital letters. But the only words I could read were these: “IF YOU” and “YOU WILL BE.”

What did it mean? There was something strange going on at the Martinez house. I had a feeling that Luke knew something about it, too, but he wasn’t talking. I was going to have to find out for myself.

I couldn’t wait to tell

my friends about Luke’s strange behavior, and the torn-up note. Both things seemed pretty mysterious, and if there’s one thing everyone in the BSC loves, it’s a mystery. But, as it turned out, I came very close to forgetting about my sitting job with the Martinezes. Why? Well, because something much more exciting happened the next day.

It all started when I came down to breakfast on Wednesday morning. Sharon smiled at me when I walked into the kitchen, and started applauding. Then my dad joined in. “There she is,” exclaimed Sharon. “Our own young celebrity! We’re proud of you, honey.” She gave me a hug.

I rubbed my eyes. I had no idea what they were talking about. For a second I thought I wasn’t really awake yet, and that this was all a weird dream. But after I’d rubbed my eyes, I found I was still standing in the middle of the kitchen, and Sharon and my dad were both still smiling at me. “Um, what are you guys talking about?” I asked. “Did I win an Oscar or something?”

“You don’t know?” asked my dad.

“Show her! Show her!” cried Sharon. She grabbed the newspaper and, folding it back to the editorial page, handed it over to me.

I took a glance, and nearly passed out. There was my name, in the middle of the page, beneath the letter I’d written on Monday after our BSC meeting. “Mary Anne Spier, Secretary, Baby-sitters Club,” it said, right there in black and white. (Kristy had convinced us that using our BSC titles would be “more impressive.”) And there was Kristy’s name and title, and Stacey’s. In fact, every one of the letters that the BSC members had written to the editor of the Stoneybrook News had been printed. They were grouped together, under a big headline that read CONCERNED YOUTH TAKE ON DEVELOPER. “Wow,” I breathed. “That was quick. Claudia took those letters down to the newspaper office only yesterday.” I felt sort of queasy. I mean, I’d written my letter because I believed the issue deserved attention, and I had been proud to sign my name. But seeing it there in print made me feel a little exposed.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

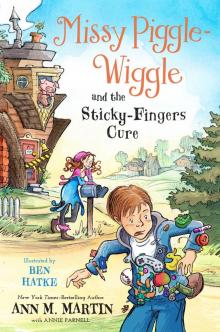

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030