- Home

- Ann M. Martin

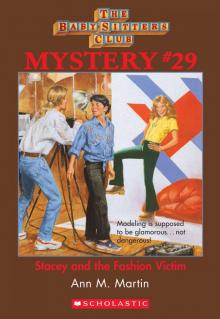

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Page 8

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Read online

Page 8

“I never meant to hurt anyone,” she said.

“I know that. But you sure scared a few people, me included.”

“Sorry,” she whispered, looking down at her feet. Then she took a quick breath and looked back into my eyes. “What are you going to do? Tell everyone? It’s my word against yours, you know. You can’t prove anything.”

“As a matter of fact,” I said, “I can. I have a few witnesses. Come on out, guys.” I turned toward the stalls. One by one, my friends emerged.

“It worked!” cried Mal.

“At least we didn’t get up at six for no reason,” said Claudia. (She hadn’t been happy about my insisting we arrive super-early at Bellair’s, but I knew it was the only way we’d catch Harmony in the act.) She grabbed a paper towel and began to scrub the lipstick off the mirror.

“Are you all right, Harmony?” Mary Anne asked, placing a gentle hand on Harmony’s shoulder.

At that, Harmony began to sniff. Then she started to cry. “How did you know it was me?” she asked between sobs.

“Do you really want to know?”

She nodded.

“Well,” I said, “once I started to put it all together, it was obvious.” I leaned against a sink and began to explain. “The thing that really tipped me off was the look on your face when Mrs. Maslin said you’d been named Princess Bellair.”

“Ugh,” said Harmony, frowning. “That was the last thing I wanted.”

“Right,” I said. “You’re sick of modeling, aren’t you? Just like Cynthia. But your mom won’t let you quit. So you tried to convince her that modeling could be very, very dangerous.” I watched Harmony’s face closely. So far, this was just a theory of mine.

Harmony gulped and nodded, and I knew my theory was correct. “I remember the first time I saw you,” I went on. “Cokie pointed you and your mother out, and told me that your mother wouldn’t rest until you were a top model. But I never had the feeling that a modeling career was that important to you. I mean, you never seemed psyched about the clothes, or the great assignments Mrs. Maslin gave you, or anything.”

Harmony was nodding. “I liked it at first,” she whispered. “It was even fun, for a while. Then I lost interest in it, but by then she — my mom — was really excited about me being a supermodel.”

“So you poisoned yourself,” I said.

My friends gasped, but Harmony just nodded. “I knew it wouldn’t kill me,” she said, “but I wanted to seem really, really sick. That’s why I drank almost the whole cup.”

“Those stomach cramps couldn’t have been much fun,” Mary Anne said sympathetically.

“They weren’t,” said Harmony. “They would have been worth it, though, if my mom had let me drop out of Fashion Week.”

“But she didn’t,” I pointed out. “So next, you started writing these notes everywhere. And putting spiders in people’s shoes.”

“And you were the one who cut up those clothes,” Mal put in.

“That’s right,” I said. “Remember those pink spots on the scissors, Mal? Well, I had suddenly remembered that Harmony’s nail polish was pink that day, too. That was a big clue.”

“I hid those scissors,” said Harmony, surprised.

“And I found them,” Mal replied proudly. “Right near the scene of the crime.”

I was watching Harmony’s face and thinking. “You know,” I said, “I remember looking at you that day and having this weird feeling that you knew who had cut up those pajamas. But at the time, I never would have thought it was you!”

“I think I even creeped myself out,” said Harmony with a tiny grin.

“Well, I know you creeped me out when you loosened the screws on that railing,” I said. “I thought I was going to be history when that thing let go.”

“I knew the other roof was there. I knew I wouldn’t be badly hurt. And I didn’t even mean for it to happen to you. I was just hoping I would fall. Anyway, how did you know I’d loosened the screws?”

“I didn’t at the time,” I said. “But I saw the screws on the roof, and later I remembered you were the one who suggested we should do the shoot over by the railing, instead of on the lounge chairs. And then I remembered the way you looked at me and said ‘sorry’ after we’d fallen.”

“Very impressive detecting,” Mal whispered, giving me a grin and a nudge.

Harmony agreed. “I can’t even pretend to be innocent,” she said. “You have all the clues. And now you have witnesses,” she went on, waving a hand at the others, “who’ve heard me say that I did all these things. And I did. I was responsible for everything.”

For a second, we were all silent.

Then Mary Anne spoke up. “You have to tell your mother,” she said. “You have to tell her you don’t want to model anymore.”

“I can’t,” said Harmony. “You don’t understand….”

“We’ll help you,” Mary Anne said, gently but firmly.

Harmony looked down at the floor. “And do we have to tell everybody what I did?”

I exchanged glances with my friends. We all seemed to feel the same way. “That’s not necessary,” I said. “As long as you promise to stop doing stuff like that.”

“I promise,” said Harmony, crossing her heart.

Just then, Cokie burst into the bathroom. “What are you all doing?” she cried. “Mrs. Maslin wants to do a run-through of tonight’s show. We’re supposed to be ready in fifteen minutes!” She ran to the mirror and began to inspect her makeup. “I don’t know why Monica uses this foundation on me,” she said to herself.

“We were just leaving,” I told her. And with that, the five of us left Cokie alone in front of the mirror — which, thanks to Claudia’s efforts, was clean.

As we walked toward the dressing room, Harmony grabbed my hand. “Thanks,” she whispered. “For catching me, I mean. I know that sounds weird, but thanks.”

I thought I understood what she meant.

She took a deep breath. “I have to talk to Mrs. Maslin,” she said. “She should let somebody else be Princess Bellair, because I don’t want to be. In fact, this show tonight is going to be the last one I ever do.”

Wow. “Do you want me to go with you?” I asked.

“No, you go ahead and get ready for the run-through,” she said. “And I know you guys,” she gestured at Mal, Mary Anne, and Claudia, “have things to do, too. Go ahead. I’ll be fine.”

She sounded sure of herself. So my friends and I went our separate ways: Mary Anne and Mal to the Kid Center, Claudia to find Jamie and Roger Bellair, and I to my mirror.

Ten minutes later, just as I finished dressing, Harmony came into the room with a smile on her face. “All set,” she said. “Mrs. Maslin said she was sorry to hear my decision, and she promised not to tell my mother until I’ve had a chance to talk to her. She said she’ll give the princess role to Blaine — which is great — and she also told me that she finally broke down and agreed to let Emily be in the show. She’s going to be a lady-in-waiting.”

Harmony was talking so fast and so happily that she didn’t even notice the warning look in my eyes. The look that said, “Watch out, your mother just came into the room.”

For, sure enough, Mrs. Skye had shown up. And she’d heard at least part of what Harmony had said.

“Tell your mother what?” she asked. “And what is this about you not being the princess?” She’d folded her arms, and she looked angry, but she was speaking very calmly. Too calmly.

Harmony gulped. “It’s just that — that —”

“Harmony, you can do it.” I’d moved next to her, and now I whispered into her ear.

“Mom, I just don’t want to model anymore,” said Harmony, in a rush. “And I’m not going to, after tonight. That’s final.”

Mrs. Skye looked shocked. “But — but —” she began.

“No,” Harmony interrupted, sounding determined. “I don’t want to do it anymore, and you can’t make me.”

“This is utter

nonsense,” said Mrs. Skye.

I’d hoped she would be more understanding. “Modeling isn’t for everyone,” I put in. “I think tonight’s going to be my last show, too.”

Mrs. Skye looked at me without really seeing me, and it was clear that she was already trying to think of some way to make Harmony reconsider. Obviously, things weren’t going to change overnight for Harmony. But at least she’d been honest about how she felt. There wouldn’t be any more fake poisonings or lipstick messages.

Harmony was going to have to work this out the hard way, but I had no doubt that she would work it out. And, if she needed us, my friends and I would be there to help.

Jessi and Becca knew a lot more about Aunt Cecelia’s smoking habits than Aunt Cecelia would ever have guessed. She was so sneaky about it, and so careful. But the fact was, they always knew when she’d had a cigarette.

“For one thing,” Jessi told us later, after the Great Stoneybrook Smokeout, “you could always smell it — on her breath, on her hands, on her clothes. Ugh!”

For another thing, they’d both noticed a pattern to Aunt Cecelia’s trips out to the garden in the Ramseys’ backyard. There was the after-breakfast trip, the late-morning trip, the after-lunch trip. You see what I mean.

(In wintertime, according to Jessi, Aunt Cecelia would open her bedroom window and lean out, puffing away. Jessi could see the clouds of smoke from her bedroom window.)

Then there were the car trips, the excuses about needing to buy milk at the convenience store, and all the times Aunt Cecelia would push back her chair after dinner and say, “Hmm, I think I’ll take a little stroll.” If Jessi or Becca asked to go with her, she’d say she was “in the mood for solitude,” and take off alone.

It wasn’t that Aunt Cecelia was a sneaky person in general. She wasn’t. Jessi knew that the main reason she snuck around with her cigarettes was that Mrs. Ramsey disapproved. She didn’t want Aunt Cecelia smoking in the house, and she definitely didn’t want Aunt Cecelia smoking in front of Jessi, Becca, and Squirt.

So Aunt Cecelia became a secret smoker.

She’d been a little surprised when Becca and Jessi approached her with the Smokeout pledge. “Heavens, girls, I hardly smoke at all!” she said. “Don’t you have any real smokers to go after?”

That’s when Jessi and Becca had presented her with a list of every cigarette she’d smoked over the last few days. (Even though they’d been at school during the day, they knew when she smoked. She stuck to her pattern.)

“Goodness,” Aunt Cecelia had said, holding the list at arm’s length so she could read it without fetching her glasses. She’d cleared her throat. “You girls have certainly done your research,” she’d said with a little smile. “I suppose it wouldn’t hurt me to try quitting for one day. Where’s a pen?”

She’d signed the pledge.

But Jessi and Becca didn’t trust her. They knew their aunt, and they knew that she had not one, but two habits that are hard to break: smoking and sneaking. Therefore, they decided in advance that they’d spy on her all day Saturday and shame her if they caught her with a cigarette. “She’d be so embarrassed if we caught her breaking her pledge,” said Jessi. “She’d probably never smoke again after that.”

She and Becca devised a plan and drew up a schedule so that one or both of them could keep an eye on Aunt Cecelia all day. Especially after breakfast, after lunch, and after dinner — Aunt Cecelia’s favorite times to smoke.

Jessi was covering the after-breakfast shift, since it was Becca’s turn to clear the table. The family had just finished a huge Saturday morning breakfast: pancakes, bacon and eggs, toast, juice, and fruit. As they sat back, satisfied and full, Jessi snuck a glance at Aunt Cecelia. She knew, just knew, that her aunt was dying for a cigarette.

Next, Jessi looked at Aunt Cecelia’s Smoke-out pledge form, which was propped up in the middle of the table. There was Aunt Cecelia’s signature. No question about it. Jessi saw Aunt Cecelia glance at the pledge. She saw Aunt Cecelia frown. Then she saw Aunt Cecelia push back from the table.

“Guess I’ll go check on my tulips,” she announced.

Jessi and Becca exchanged a glance. Neither one of them moved a muscle. Jessi waited until Aunt Cecelia left the room. Then she stretched, as casually as possible, and stood up herself. “Great pancakes, Dad,” she said as she picked up her plate and glass and took them over to the sink. “Guess I’ll go check on my … my toe shoes.” She and Becca had agreed that it would probably be best if their parents didn’t know about the spying they’d planned to do.

Jessi tiptoed down the hall, listening for Aunt Cecelia’s footsteps. There was no sound, so Jessi figured she must already have slipped out the sliding glass doors that lead from the Ramsey dining room to the backyard. Jessi headed for those same doors.

She slid them open quietly and tiptoed out onto the deck.

“Looking for someone?”

Jessi jumped. Then she turned and saw Aunt Cecelia glaring at her.

“Don’t trust your old aunt, huh?” asked Aunt Cecelia. She had one hand on her hip and the other behind her back, and she sounded angry. Jessi didn’t know what to say.

Then Aunt Cecelia laughed. “I can’t blame you, honey,” she said. “I am just about the sneakiest smoker ever. But when I signed that pledge, I meant it.”

Jessi wanted to believe Aunt Cecelia, but she was still just the tiniest bit suspicious. She took a step closer and tried to sniff without Aunt Cecelia noticing. After all, what was Aunt Cecelia hiding behind her back, if not a cigarette?

Aunt Cecelia laughed again and brought her hand around to the front. She was holding a large bouquet of bright red tulips.

The only thing Jessi could smell was their faintly sweet scent, and the only thing she could think to say was, “Oops. Sorry.” Then she hugged Aunt Cecelia.

“You know, honey,” said Aunt Cecelia, “this Smokeout is such a good idea that I think I’m going to try it again tomorrow. What do you think of that?”

Jessi smiled up at her. “I think that would be excellent,” she said. “Totally excellent.”

On Saturday morning, Watson showed up for breakfast wearing a tux.

“Jacket,” Kristy told us later, “pants, starched white shirt, black bow tie, plaid cummerbund — or whatever you call those things — and shiny black shoes. The whole outfit.”

The family was gathered around the huge kitchen table: Kristy’s mom, Nannie, Charlie and Sam, David Michael, Karen, Andrew, and Emily Michelle. The room had been full of noisy talk and the clatter of dishes. When Watson showed up there was a sudden, shocked silence.

Then, after a few seconds, everybody started talking at once.

“Um, Daddy? Are you going to a wedding or something?” Karen wanted to know.

“Did we have plans I’ve forgotten about?” Kristy’s mom asked, sounding panicked.

“Looking good, Watson,” Kristy said, grinning and giving him the thumbs-up.

“Sharp threads, man,” agreed Charlie, nodding.

“Can I borrow that suit for my prom?” asked Sam.

Emily Michelle just stared at Watson as if he were some stranger she’d never seen before.

Watson stood there, looking as if he were about to burst out laughing. “I want you all to finish breakfast and then run upstairs and dress in your best clothes,” he said when he could fit a word in. “I’m having a little ceremony this morning, and I want you all to be there.”

It was then that Kristy noticed the ornately carved wooden box Watson had tucked beneath his arm. “What’s in the box?” she asked.

“Some very good companions,” Watson answered. “Companions I’m going to be saying good-bye to.”

That was all he’d say. He waved away their questions as he toasted and buttered a bagel. “The sooner you’re all dressed, the sooner we can begin,” he told them.

They finished breakfast in record time. Kristy’s mom said it was okay to leave the dirty dishes on the table for once. T

hen everybody headed upstairs to figure out what to wear.

Kristy doesn’t enjoy dressing up, which meant it wasn’t hard to decide between the two fancy dresses she owns, both of which are left over from weddings. She scrambled into one of them, ran a brush through her hair, debated whether to wear pantyhose and decided not to, stuck her feet into the one pair of shoes she owns that aren’t sneakers, and ran back downstairs without even checking herself in the mirror.

Watson waited until everyone was assembled in the front hall. Charlie and Sam came downstairs dressed in suits. David Michael had dressed in a polo shirt and khakis. Andrew was wearing a clean shirt and his newest jeans, and Karen had pulled on a frilly pink dress. Kristy’s mom had dressed Emily Michelle in a white jumper, and herself in a full-length black gown she’s worn to fancy charity dinners.

“You all look very nice,” Watson said. “Thank you. And now, will you accompany me outside?” He bowed and offered his arm to his wife. Then the two of them led the others into the backyard.

Beneath one of the apple trees was a small but deep hole, surrounded by cut flowers arranged into bright bouquets. Watson asked his family to stand in a circle around the hole.

“We are gathered here today,” he said solemnly, “to bid good-bye to …” he paused and flipped open the box, “… to some very dear friends.”

“Watson! Your expensive cigars!” said Kristy’s mom.

True enough. The box was full of cigars, each with a colorful ring. Kristy could smell their rich scent.

“That’s right,” said Watson. “I’ve been saving these for a special occasion, and I think that special occasion is now. But instead of smoking them, I’m going to put them to rest for good.” He glanced wistfully at the cigars. Then he took one last sniff, smiled sadly, and closed the box. He knelt down and placed it in the hole he’d dug. Then he picked up the hose, which was lying nearby. “This is just to make sure I don’t sneak out here and dig them up some night when I’m feeling weak,” he explained as he held the nozzle over the box. “Charlie, would you turn on the faucet?”

So that was Kristy’s Smokeout memory: Watson in a tux, surrounded by well-dressed family members, holding a hose over a box of very valuable cigars. “I didn’t even think of taking a picture,” she said later, “but I guess I don’t need one. I’ll never forget that image.”

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030