- Home

- Ann M. Martin

Better to Wish Page 8

Better to Wish Read online

Page 8

“Happy Valentine’s Day,” he said, “one day late.” He withdrew his arm and loped ahead of Abby and Rose, along the sidewalk and across the lawn to his front door. Abby watched him, thinking that he moved very gracefully for a boy, and noticing that his jaw had grown squarer and his shoulders broader.

“Abby has a boyfriend!” Rose chanted when Zander was out of earshot.

“No, I don’t.”

Later, after Abby had lugged Fred back inside and was taking off his jacket, she heard a crinkling sound and reached into the pocket of her coat. Her hand closed around an envelope. She pulled it out and saw her name in neat printing. ABIGAIL.

She waited until she was alone in her room to open it, and inside she found a card showing a girl and boy joyfully riding a giant bumblebee, the words Valentine, I’m abuzz over you trailing in the wake of the bee. She flipped the card open. Zander had written BEE MINE, ZANDER in the same neat handwriting.

Abby frowned, then smiled, and added the card to the ones she’d received from Rose and Sarah the day before.

She hadn’t dared to give Zander a Valentine.

“It snowed!” Rose announced. “Abby, it snowed last night!”

Abby sat up fast, tossing her covers back, and knelt on her window seat. Snow covered the ground and the branches of the trees and the roof of Zander’s house.

“Ha!” said Rose from the doorway. “You’re using the snow as an excuse to look in Zander’s window.”

“I am not,” said Abby, which was a lie. She liked any excuse at all to see what might be going on in Zander’s room. Sometimes she watched him writing at his desk and sometimes she watched him lifting weights, which he did because his older brothers told him he was as scrawny as a chicken. This was absolutely untrue. But sometimes, like now, the blind was drawn, and then Abby felt unreasonably shut out and disappointed.

“His blind is down,” she said, and flopped back on her bed.

Rose hesitated in the doorway. “Mama’s talking about the babies again,” she whispered.

“What?”

“The babies. The ones God took.”

Abby sighed. “I don’t know what to do about that.”

“Why can’t she be satisfied with her living children?” asked Rose, twisting the end of one braid around her finger. “She has us, and she has Fred, and she has Adele, who actually is a baby. But she’s been outside, covering up the rosebushes and wondering why God took her babies. Pop saw her and yanked her arm and said, ‘Go in the house, the neighbors are watching,’ because Mama was only wearing her nightie and a pair of boots.”

Abby closed her eyes briefly and Rose sat on the end of her bed. “Don’t worry. Sheila’s taking care of Fred and Adele,” said Rose cautiously, trying to gauge her sister’s mood.

“It’s almost Christmas. I thought the holidays would make Mama feel better.”

“So did I,” Rose replied.

“Maybe … I don’t know.”

“I wanted to make gingerbread today.”

“Ellen will help you.”

“I wanted to make gingerbread with Mama.”

Abby gave her sister a small smile. “Sarah’s coming over later. Her parents are going to do some Christmas shopping in town. Maybe Sarah and I will go into town, too. Want to come with us?”

Rose nodded. “Okay. Thanks.”

Sarah arrived just before lunch. “Bye, Mother. Bye, Dad,” she called as the Moresides waved from the windows of their car.

“How long can you stay?” Abby asked her.

“Mother said they’ll be busy for three or four hours. Let’s go play with the baby first. Please? Can I hold her?”

“In a bit,” said Abby. “She’s napping now.”

“You’re so lucky to have a brother and sisters.”

“Yeah,” said Rose, “but at your house on Christmas morning, you get all the presents.”

“Rose?” called Pop’s voice from the parlor. “That sounded greedy.”

Rose looked at the floor. “Sorry, Pop,” she replied.

Lunch was chicken soup and cinnamon toast served at the kitchen table, Fred kicking his heels noisily against his high chair. Abby’s parents ate in the dining room, much to the girls’ relief.

“Done!” Rose cried suddenly, drinking the last swallow of soup directly from her bowl. She cast a nervous glance toward the dining room. “Let’s go now.”

“Where are we going?” asked Sarah.

“Into town?” Abby suggested.

“Let’s play in the snow first,” said Rose. “We’ve hardly had any snow so far.”

This was true. Except for a surprise snowfall in the middle of October, the autumn had been unusually mild.

“What do you want to do?” Abby asked Sarah.

Sarah screwed up her face. “Take a walk?” she said finally.

“Take a walk?!” exclaimed Rose, dismayed. “You sound like the grown-ups.” But when Abby and Sarah bundled up and left the house, she followed them.

Snow had started to fall again, and Abby and Sarah scuffed through it in their lace-up boots. “Are you going to walk with us or not?” Abby shouted, without turning around.

“How did you know I was here?” Rose called.

“You’re noisy. Come on. Catch up.”

“Are you going to talk about boys?”

Sarah laughed. “What boys?”

“Any boys.”

“No. We’re talking about what we want for Christmas.”

“I want a dog,” said Rose, hurrying to Abby’s side.

“A sister,” said Sarah.

“Poetry books,” said Abby.

“You just want poetry books because Zander likes poetry,” said Rose.

The girls emerged from a grove of fir trees at the western edge of town and found themselves at the top of a small hill.

“Look, there’s Miller’s Pond,” said Sarah, pointing to the bottom of the hill. “Last one there’s a rotten egg.”

Sarah took off down the hill, slipping in the snow and laughing, her legs pumping faster and faster. Abby and Rose ran after her. At the bottom of the hill, Abby skidded to a stop, Rose running into her, but Sarah kept going and called breathlessly over her shoulder, “I’ll bet the pond’s frozen now!”

“No, it isn’t!” Abby called back. “Not after one snowstorm! Sarah, stop!”

“Stop, stop!” shouted Rose.

But Sarah laughed and sped up, and when she reached the old, ragged stalks of cattails at the edge of the pond, she leaped through them, skidding across the fragile sheet of ice that had formed. Abby could see puddles of water around some of the cattails and she remembered the previous winter when she and Zander and Rose had stood at this same spot after school one day and watched a dog step curiously onto the snowy pond and fall through the ice. He’d made only a small splash and then had struggled and thrashed while Abby and Zander had run to him. Zander had reached him first, just as the dog had heaved himself up the bank and bolted away, stopping to shake himself at the edge of the woods.

Sarah was far beyond the edge of the pond when Abby heard a low creaking sound, and then Sarah’s feet disappeared, swallowed by the snow and ice and frigid water. Her coat billowed up around her waist like the parachutes Abby had seen in newsreels at the picture show.

“Sarah!” Rose shouted again. “Sarah!”

Abby ran to the cattails and placed one boot tentatively on the snow.

“No, Abby!” Rose called. “Don’t go out there.”

“She can’t swim,” said Abby. She set her foot more firmly on the snow and felt her boot fill with water. She pulled her foot out. Then she looked to Sarah — but Sarah wasn’t there.

Rose whispered, “She’s gone.”

Abby stepped back and stared across the pond. She shaded her eyes from the glare of the snow and the milk-white sky. She heard nothing but the lapping of water under ice.

“Sarah?” she said tentatively.

Beside her, Rose began jumping

up and down. “Sarah, Sarah, Sarah!”

Abby stepped onto the ice again, but Rose jerked her back. “Don’t! You’ll go under, too. The water’s freezing. We have to get help.”

“I can’t leave her.” Abby’s breath came in short gasps and she felt her throat tighten. “Sarah!” she called again.

Rose was already running up the hill. “You stay right there, Abby, so we’ll know where she went in the water. But don’t go in. I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

Abby sank into the snow. Then she stood up and looked for a branch. She had read in storybooks about drowning children being pulled from ponds by grabbing on to branches held out to them by rescuers. But there was no sign of Sarah, no one for Abby to pull ashore. She sat in the snow again, waiting for Sarah to emerge, for Sarah to jump out of the water like the dog had, for Sarah to run laughing along the bank and say it was all a joke. After a time, there was a great commotion on the hill above and then a crowd of men, followed by several women and a group of gawking, fascinated children, came running down to the pond. Pop was with the men. When he saw Abby, he folded her in his arms and hugged her to his chest fiercely.

The people — later Abby could never say exactly who they were; they were just people — shouted and ran along the bank, and then other people arrived with blankets and a stretcher. After Abby and Rose had explained — tearfully and with lots of gesturing — everything that they knew, Pop took a look around and started to lead them back up the hill.

“I want to stay!” cried Abby.

“No,” Pop replied quietly.

“I can’t walk anymore,” said Rose suddenly, and plopped down, sitting in the snow. Abby noticed that her sister had lost her hat.

Pop said nothing more, but picked Rose up and carried her through the woods and back to Haddon Road, Abby trailing behind. At the bottom of their street, he set Rose down and took Abby by the hand.

“Do Mr. and Mrs. Moreside know?” she whispered.

“Someone went to find them.”

“But do they know?” Abby persisted.

And Rose said, “Is she dead?”

“I don’t have the answers,” said Pop, and his voice was gentle.

Abby didn’t ask any more questions. She stepped dazedly along, between her father and Rose. They passed the Evanses’, where Abby thought she could feel eyes peering from behind curtains, and eventually Zander’s house, where Zander himself was standing on the porch, watching them solemnly.

“It wasn’t our fault,” Abby wanted to say. But she stared at the ground and watched her boots and Pop’s boots, matched her stride to his, and she and Rose and Pop walked wordlessly into their house.

Mama met them at the door and said nothing, but she gathered Rose and Abby into her arms. Abby didn’t know how everyone had heard about Sarah, but it was plain that the news had already traveled halfway around Barnegat Point. She leaned back to look at Mama and asked again, “Do Mr. and Mrs. Moreside know?”

Mama and Pop exchanged a glance.

“Yes, they know,” Mama said after a moment.

“Have they found her yet?”

“I don’t think so,” said Mama.

“Then maybe she’s still alive,” said Rose.

No one answered her.

Sarah’s funeral was held three days later, on Christmas Eve at the little church in Lewisport. The church was decorated for the Christmas service, garlands of pine branches and red bows along the aisle, the Nativity arranged outside by the front door. Abby, Rose, Mama, and Pop sat five pews behind Sarah’s parents. Mrs. Moreside cried during the entire service. Mr. Moreside placed his arm across his wife’s shoulders and stared straight ahead at the minister, from the time the service began until at last it was over. Then he didn’t move until someone — Sarah’s uncle? — touched him on the shoulder.

The Moresides walked down the aisle, followed by Sarah’s grandparents and aunts and uncles and cousins. When Mrs. Moreside passed Abby’s family, she turned and glared at them.

“It wasn’t our fault,” whispered Abby. “She was my best friend.”

Mama took her hand and held it until the four of them had climbed into their car and were heading back to Barnegat Point.

Sometimes when Abby walked, alone, through Barnegat Point to the high school, she imagined that the other girls, walking in pairs or in laughing, noisy groups, were talking about her.

“Remember Sarah, that girl from Lewisport who drowned in Miller’s Pond? She was Abby Nichols’s friend. Her best friend.”

“Have you seen her brother? He’s a cripple. He’s four years old and he can’t walk yet. My aunt said he’s an idiot, too.”

“Her mother’s crazy. There’s something wrong in that family.”

“And her father is mean! He fired my father just for being late.”

Abby longed for the days of walking to the grammar school with Rose and meeting up with Sarah and Orrin. At the beginning of eighth grade she and Sarah had felt like queens. The eighth graders were the most important students in the entire school. They could boss the younger kids around and brag about going to the high school the next year. The teachers gave them special privileges — they were allowed to walk into town at lunchtime if they had permission from their parents — and they were in charge of the Christmas program and the spring carnival. Then in June they got to have an actual graduation ceremony.

All during that autumn, Abby and Sarah had gleefully walked to the drugstore and eaten sandwiches at the soda fountain anytime Sarah had saved enough money to buy lunch. In December they’d been elected co-authors of the Christmas program and together had written a play about a lost lamb and a shepherd and how the star that shone in the sky on the night Jesus was born had cast enough light to help the shepherd find the lamb, which later grew up to save the shepherd’s life. The play had been a big hit. Two days later Sarah had drowned and Abby, without a best friend, without Orrin, had crept through the remainder of the school year, a solitary, marked figure. She had become “the girl whose best friend drowned.” Rose still walked to and from school with her, of course, and occasionally Zander tried to talk to her. But Abby felt as if she were wearing a sign that proclaimed her new sad status, and she didn’t know how to erase the words on the sign.

What she remembered most about the next few months was the quiet. People tended to be quiet around her, and she was quiet in return. Her teachers were solicitous and forgiving. The other girls in her class spoke to her sweetly and slipped her apples and hard candies and little notes. Until they didn’t anymore. Until they were more interested in seeing who got Valentine cards from boys, and in buying fabric to make dresses for the spring cotillion, and in being elected to the planning committee for the spring carnival.

Abby walked to school with Rose, sat silently in her classroom, came home, did her homework, then sat at her desk and wrote stories and poems and glued them into a scrapbook.

On graduation day she won three of the five academic awards: for composition, for history, and for overall highest grades. She smiled at the principal and thanked him politely, walked home with her family, and spent the summer reading and writing, taking care of Adele, and trying to teach Fred to walk. She found that she cared about little else, including Zander, who, at the beginning of the summer, would sometimes turn up on the Nicholses’ porch and sit quietly in the swing, hoping (according to Rose, who seemed to know everything) that Abby would come outside and join him. But Abby watched him from the parlor and discovered that she felt as listless then as she did at any other time, and eventually Zander stopped coming by.

And now it was autumn again and she was a freshman at the Barnegat Point high school — a lowly freshman on the bottom rung of the ladder. There was no Rose to walk with, and no Sarah or Orrin to greet her at the gathering spot on the lawn.

“Are you going to spend the entire year mooning around?” asked Ellen when Abby sank down at the kitchen table after school one day, a stack of books at her elbow.

Abby frowned. “What?”

Ellen turned from the stove and faced her. “For pity’s sake, honey, Sarah is the one who drowned, not you. You’ve got your whole life ahead. Stop wasting it.”

“I —” said Abby. Tears sprang to her eyes.

“Go ahead and cry. Lord knows you’ve been through enough. But then you’d better get on with things. I’m speaking plain because no one else seems willing to. They’re all still tiptoeing around like you’ll break. But I know a thing or two, and you’ll break if you don’t sit yourself up and get going again. Isn’t there something you want to do this year besides schoolwork?”

Abby shook her head.

“There’s got to be something. A play or a club? And what about friends? A nice girl like you should have plenty of friends.”

“I don’t know.”

“It isn’t easy to find new friends, but you have to make some kind of effort. You’re never going to find friends by sitting at your desk or wheeling Adele up and down the street in the carriage.”

Abby poked at a cookie that Ellen had set before her. “I saw a sign for the glee club,” she ventured.

“Well, that’s wonderful. I was in the glee club when I was in school.”

Abby had a hard time imagining Ellen as a girl, slim hipped and giggling, standing shoulder to shoulder with her glee club friends. “Really?”

“Yes.”

“I saw a sign for the school annual, too,” Abby went on. “I’d love to work on the annual.”

“There you go. Now, tomorrow, when you get to school, you do whatever it is you have to do to try out for the glee club and work on the annual.”

“All right.” Abby brightened. Not even the sight of her mother in bed in the middle of the afternoon could dampen her spirits. The next day, feeling resolute, if not exactly cheerful, she found a sign about glee club tryouts and decided to sing “Amazing Grace” as her audition piece. And she signed up to work on the Barnegat Point Central High School 1936–37 Annual.

Karen's Tea Party

Karen's Tea Party Kristy and the Snobs

Kristy and the Snobs Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Karen's Kittens

Karen's Kittens Karen's Big Job

Karen's Big Job Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street

Claudia and the Genius of Elm Street The Fire at Mary Anne's House

The Fire at Mary Anne's House Science Fair

Science Fair Me and Katie (The Pest)

Me and Katie (The Pest) Karen's Plane Trip

Karen's Plane Trip Jessi's Wish

Jessi's Wish Dawn and Too Many Sitters

Dawn and Too Many Sitters Jessi and the Jewel Thieves

Jessi and the Jewel Thieves Eleven Kids, One Summer

Eleven Kids, One Summer Karen's Goldfish

Karen's Goldfish Snow War

Snow War Abby and the Secret Society

Abby and the Secret Society Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye

Good-Bye Stacey, Good-Bye Karen's Sleepover

Karen's Sleepover Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby

Claudia and the World's Cutest Baby Mary Anne Saves the Day

Mary Anne Saves the Day Mallory and the Dream Horse

Mallory and the Dream Horse Kristy and the Mystery Train

Kristy and the Mystery Train Dawn's Family Feud

Dawn's Family Feud Karen's Twin

Karen's Twin Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn

Little Miss Stoneybrook... And Dawn Karen's Mistake

Karen's Mistake Karen's Movie Star

Karen's Movie Star Mallory and the Mystery Diary

Mallory and the Mystery Diary Karen's Monsters

Karen's Monsters Kristy + Bart = ?

Kristy + Bart = ? Karen's Dinosaur

Karen's Dinosaur Here Today

Here Today Karen's Carnival

Karen's Carnival How to Look for a Lost Dog

How to Look for a Lost Dog Stacey vs. Claudia

Stacey vs. Claudia Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend

Stacey's Ex-Boyfriend Here Come the Bridesmaids!

Here Come the Bridesmaids! Graduation Day

Graduation Day Kristy's Big News

Kristy's Big News Karen's School Surprise

Karen's School Surprise Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer

Kristy Thomas, Dog Trainer Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller

Baby-Sitters' Christmas Chiller Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation

Baby-Sitters' Winter Vacation Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life Claudia and the Bad Joke

Claudia and the Bad Joke Mary Anne's Makeover

Mary Anne's Makeover Stacey and the Fashion Victim

Stacey and the Fashion Victim Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schafer, Undercover Baby-Sitter Karen's Tuba

Karen's Tuba Dawn's Wicked Stepsister

Dawn's Wicked Stepsister Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Three: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Nanny

Karen's Nanny Jessi and the Awful Secret

Jessi and the Awful Secret Karen's New Year

Karen's New Year Karen's Candy

Karen's Candy Karen's President

Karen's President Mary Anne and the Great Romance

Mary Anne and the Great Romance Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies

Mary Anne + 2 Many Babies Kristy and the Copycat

Kristy and the Copycat Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter

Jessi and the Bad Baby-Sitter Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade

Claudia, Queen of the Seventh Grade Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost

Claudia and the Lighthouse Ghost Karen's New Puppy

Karen's New Puppy Karen's Home Run

Karen's Home Run Karen's Chain Letter

Karen's Chain Letter Kristy in Charge

Kristy in Charge Karen's Angel

Karen's Angel Mary Anne and Too Many Boys

Mary Anne and Too Many Boys Karen's Big Fight

Karen's Big Fight Karen's Spy Mystery

Karen's Spy Mystery Stacey's Big Crush

Stacey's Big Crush Karen's School

Karen's School Claudia and the Terrible Truth

Claudia and the Terrible Truth Karen's Cowboy

Karen's Cowboy The Summer Before

The Summer Before Beware, Dawn!

Beware, Dawn! Belle Teale

Belle Teale Claudia's Big Party

Claudia's Big Party The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

The Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Karen's Book

Karen's Book Teacher's Pet

Teacher's Pet Boy-Crazy Stacey

Boy-Crazy Stacey Claudia and the Disaster Date

Claudia and the Disaster Date Author Day

Author Day Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye

Claudia and the Sad Good-Bye Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever

Kristy and the Worst Kid Ever Yours Turly, Shirley

Yours Turly, Shirley Class Play

Class Play Kristy and the Vampires

Kristy and the Vampires Kristy and the Cat Burglar

Kristy and the Cat Burglar Karen's Pumpkin Patch

Karen's Pumpkin Patch Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery at the Empty House Karen's Chicken Pox

Karen's Chicken Pox Mary Anne and the Playground Fight

Mary Anne and the Playground Fight Stacey's Mistake

Stacey's Mistake Coming Apart

Coming Apart Mary Anne and the Little Princess

Mary Anne and the Little Princess Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers

Karen, Hannie and Nancy: The Three Musketeers 'Tis the Season

'Tis the Season Claudia and Mean Janine

Claudia and Mean Janine Karen's School Bus

Karen's School Bus Mary Anne's Big Breakup

Mary Anne's Big Breakup Rain Reign

Rain Reign Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum

Claudia and the Mystery at the Museum Claudia and the Great Search

Claudia and the Great Search Karen's Doll

Karen's Doll Shannon's Story

Shannon's Story Sea City, Here We Come!

Sea City, Here We Come! Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook

Stacey and the Mystery of Stoneybrook Karen's Treasure

Karen's Treasure Ten Rules for Living With My Sister

Ten Rules for Living With My Sister With You and Without You

With You and Without You Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure

Baby-Sitters' Island Adventure Karen's Fishing Trip

Karen's Fishing Trip Dawn and the Big Sleepover

Dawn and the Big Sleepover New York, New York!

New York, New York! Ten Kids, No Pets

Ten Kids, No Pets Happy Holidays, Jessi

Happy Holidays, Jessi Halloween Parade

Halloween Parade Karen's New Holiday

Karen's New Holiday Kristy Power!

Kristy Power! Karen's Wish

Karen's Wish Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting

Claudia and the Mystery in the Painting Karen's Stepmother

Karen's Stepmother Abby in Wonderland

Abby in Wonderland Karen's Snow Day

Karen's Snow Day Kristy and the Secret of Susan

Kristy and the Secret of Susan Karen's Pony Camp

Karen's Pony Camp Karen's School Trip

Karen's School Trip Mary Anne to the Rescue

Mary Anne to the Rescue Karen's Unicorn

Karen's Unicorn Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade

Stacey and the Haunted Masquerade Claudia Gets Her Guy

Claudia Gets Her Guy Missing Since Monday

Missing Since Monday Stacey's Choice

Stacey's Choice Stacey's Ex-Best Friend

Stacey's Ex-Best Friend Karen's New Teacher

Karen's New Teacher Karen's Accident

Karen's Accident Karen's Lucky Penny

Karen's Lucky Penny Karen's Cartwheel

Karen's Cartwheel Karen's Puppet Show

Karen's Puppet Show Spelling Bee

Spelling Bee Stacey's Problem

Stacey's Problem Stacey and the Stolen Hearts

Stacey and the Stolen Hearts Karen's Surprise

Karen's Surprise Karen's Worst Day

Karen's Worst Day The Ghost at Dawn's House

The Ghost at Dawn's House Karen's Big Sister

Karen's Big Sister Karen's Easter Parade

Karen's Easter Parade Mary Anne and the Silent Witness

Mary Anne and the Silent Witness Karen's Swim Meet

Karen's Swim Meet Mary Anne's Revenge

Mary Anne's Revenge Karen's Mystery

Karen's Mystery Stacey and the Mystery Money

Stacey and the Mystery Money Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs

Dawn and the Disappearing Dogs Karen's Christmas Tree

Karen's Christmas Tree Welcome to Camden Falls

Welcome to Camden Falls Karen's Pilgrim

Karen's Pilgrim Dawn and the Halloween Mystery

Dawn and the Halloween Mystery Mary Anne in the Middle

Mary Anne in the Middle Karen's Toys

Karen's Toys Kristy's Great Idea

Kristy's Great Idea Claudia and the Middle School Mystery

Claudia and the Middle School Mystery Karen's Big Weekend

Karen's Big Weekend Logan's Story

Logan's Story Karen's Yo-Yo

Karen's Yo-Yo Kristy's Book

Kristy's Book Mallory and the Ghost Cat

Mallory and the Ghost Cat Mary Anne and the Music

Mary Anne and the Music Karen's Tattletale

Karen's Tattletale Karen's County Fair

Karen's County Fair Karen's Mermaid

Karen's Mermaid Snowbound

Snowbound Karen's Movie

Karen's Movie Jessi and the Troublemaker

Jessi and the Troublemaker Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake

Baby-Sitters at Shadow Lake Mallory on Strike

Mallory on Strike Jessi's Baby-Sitter

Jessi's Baby-Sitter Karen's Leprechaun

Karen's Leprechaun Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls

Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls Karen's Good-Bye

Karen's Good-Bye Karen's Figure Eight

Karen's Figure Eight Logan Likes Mary Anne!

Logan Likes Mary Anne! Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery

Mary Anne and the Zoo Mystery Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure Dawn on the Coast

Dawn on the Coast Stacey and the Cheerleaders

Stacey and the Cheerleaders Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph

Claudia and the Clue in the Photograph Karen's New Friend

Karen's New Friend Mallory and the Trouble With Twins

Mallory and the Trouble With Twins Karen's Roller Skates

Karen's Roller Skates Abby and the Best Kid Ever

Abby and the Best Kid Ever Poor Mallory!

Poor Mallory! Karen's Witch

Karen's Witch Karen's Grandmothers

Karen's Grandmothers Slam Book

Slam Book Karen's School Picture

Karen's School Picture Karen's Reindeer

Karen's Reindeer Kristy's Big Day

Kristy's Big Day The Long Way Home

The Long Way Home Karen's Sleigh Ride

Karen's Sleigh Ride On Christmas Eve

On Christmas Eve Karen's Copycat

Karen's Copycat Karen's Ice Skates

Karen's Ice Skates Claudia and the Little Liar

Claudia and the Little Liar Abby the Bad Sport

Abby the Bad Sport The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three

The Baby-Sitters Club #5: Dawn and the Impossible Three Abby's Book

Abby's Book Karen's Big Top

Karen's Big Top Main Street #8: Special Delivery

Main Street #8: Special Delivery Kristy and the Kidnapper

Kristy and the Kidnapper Karen's Ski Trip

Karen's Ski Trip Karen's Hurricane

Karen's Hurricane Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall

Stacey and the Mystery at the Mall Jessi and the Superbrat

Jessi and the Superbrat Kristy and the Baby Parade

Kristy and the Baby Parade Karen's New Bike

Karen's New Bike Karen's Big City Mystery

Karen's Big City Mystery Baby-Sitters' European Vacation

Baby-Sitters' European Vacation Hello, Mallory

Hello, Mallory Dawn's Big Date

Dawn's Big Date Karen's Christmas Carol

Karen's Christmas Carol Jessi's Horrible Prank

Jessi's Horrible Prank Kristy and the Missing Fortune

Kristy and the Missing Fortune Kristy and the Haunted Mansion

Kristy and the Haunted Mansion Jessi's Big Break

Jessi's Big Break Karen's Pony

Karen's Pony Welcome Home, Mary Anne

Welcome Home, Mary Anne Stacey the Math Whiz

Stacey the Math Whiz September Surprises

September Surprises Bummer Summer

Bummer Summer Karen's Secret

Karen's Secret Abby's Twin

Abby's Twin Main Street #4: Best Friends

Main Street #4: Best Friends Karen's Big Move

Karen's Big Move Mary Anne Misses Logan

Mary Anne Misses Logan Stacey's Book

Stacey's Book Claudia and the Perfect Boy

Claudia and the Perfect Boy Holiday Time

Holiday Time Stacey's Broken Heart

Stacey's Broken Heart Karen's Field Day

Karen's Field Day Kristy's Worst Idea

Kristy's Worst Idea Dawn and the Older Boy

Dawn and the Older Boy Karen's Brothers

Karen's Brothers Claudia's Friend

Claudia's Friend Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore

Mary Anne and the Haunted Bookstore Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever

Dawn and Whitney, Friends Forever Summer School

Summer School Karen's Birthday

Karen's Birthday Karen's Black Cat

Karen's Black Cat Stacey McGill... Matchmaker?

Stacey McGill... Matchmaker? Claudia's Book

Claudia's Book Main Street #2: Needle and Thread

Main Street #2: Needle and Thread Karen's Runaway Turkey

Karen's Runaway Turkey Karen's Campout

Karen's Campout Karen's Bunny

Karen's Bunny Claudia and the New Girl

Claudia and the New Girl Karen's Wedding

Karen's Wedding Karen's Promise

Karen's Promise Karen's Snow Princess

Karen's Snow Princess Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Dropout Starring the Baby-Sitters Club!

Starring the Baby-Sitters Club! Kristy for President

Kristy for President California Girls!

California Girls! Maid Mary Anne

Maid Mary Anne Abby's Un-Valentine

Abby's Un-Valentine Stacey's Secret Friend

Stacey's Secret Friend Karen's Haunted House

Karen's Haunted House Claudia and Crazy Peaches

Claudia and Crazy Peaches Karen's Prize

Karen's Prize Get Well Soon, Mallory!

Get Well Soon, Mallory! Karen's Doll Hospital

Karen's Doll Hospital Karen's Newspaper

Karen's Newspaper Karen's Toothache

Karen's Toothache Mary Anne and Miss Priss

Mary Anne and Miss Priss Abby's Lucky Thirteen

Abby's Lucky Thirteen The Secret Book Club

The Secret Book Club The All-New Mallory Pike

The All-New Mallory Pike Karen's Turkey Day

Karen's Turkey Day Karen's Magician

Karen's Magician Mary Anne and the Library Mystery

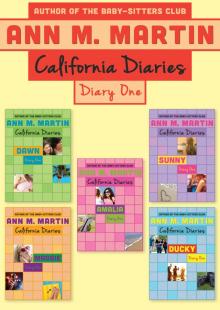

Mary Anne and the Library Mystery Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary One: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic

Mary Anne and the Secret in the Attic Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise

Kristy and the Mother's Day Surprise Karen's in Love

Karen's in Love Welcome to the BSC, Abby

Welcome to the BSC, Abby Karen's Kittycat Club

Karen's Kittycat Club The Mystery at Claudia's House

The Mystery at Claudia's House The Truth About Stacey

The Truth About Stacey Karen's Bully

Karen's Bully Karen's Gift

Karen's Gift BSC in the USA

BSC in the USA Everything for a Dog

Everything for a Dog Dawn and the We Love Kids Club

Dawn and the We Love Kids Club Karen's Ghost

Karen's Ghost Stacey's Lie

Stacey's Lie Jessi's Secret Language

Jessi's Secret Language Kristy and the Missing Child

Kristy and the Missing Child Better to Wish

Better to Wish Baby-Sitters on Board!

Baby-Sitters on Board! Kristy at Bat

Kristy at Bat Everything Changes

Everything Changes Don't Give Up, Mallory

Don't Give Up, Mallory A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray

A Dog's Life: The Autobiography of a Stray Karen's Big Lie

Karen's Big Lie Karen's Show and Share

Karen's Show and Share Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym)

Mallory Hates Boys (and Gym) Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky

Diary Two: Dawn, Sunny, Maggie, Amalia, and Ducky Karen's Pen Pal

Karen's Pen Pal Claudia and the Friendship Feud

Claudia and the Friendship Feud Karen's Secret Valentine

Karen's Secret Valentine Keep Out, Claudia!

Keep Out, Claudia! Aloha, Baby-Sitters!

Aloha, Baby-Sitters! Welcome Back, Stacey

Welcome Back, Stacey Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter

Jessi Ramsey, Pet-Sitter Karen's Pizza Party

Karen's Pizza Party Kristy and the Dirty Diapers

Kristy and the Dirty Diapers Staying Together

Staying Together Dawn and the Surfer Ghost

Dawn and the Surfer Ghost Claudia Makes Up Her Mind

Claudia Makes Up Her Mind Jessi's Gold Medal

Jessi's Gold Medal Karen's Kite

Karen's Kite Baby Animal Zoo

Baby Animal Zoo Dawn's Big Move

Dawn's Big Move Karen's Big Joke

Karen's Big Joke Karen's Lemonade Stand

Karen's Lemonade Stand Ma and Pa Dracula

Ma and Pa Dracula Baby-Sitters' Haunted House

Baby-Sitters' Haunted House Abby and the Mystery Baby

Abby and the Mystery Baby Home Is the Place

Home Is the Place Karen's Grandad

Karen's Grandad Twin Trouble

Twin Trouble Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far)

Ten Good and Bad Things About My Life (So Far) Diary Two

Diary Two Baby-Sitters Club 027

Baby-Sitters Club 027 Claudia and the Mystery Painting

Claudia and the Mystery Painting Diary One

Diary One Baby-Sitters Club 037

Baby-Sitters Club 037 Baby-Sitters Club 028

Baby-Sitters Club 028 Baby-Sitters Club 085

Baby-Sitters Club 085 Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter

Dawn Schaffer Undercover Baby-Sitter Jessi's Babysitter

Jessi's Babysitter The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #110: Abby the Bad Sport (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Karen's Little Sister

Karen's Little Sister Baby-Sitters Club 058

Baby-Sitters Club 058 Claudia And The Genius On Elm St.

Claudia And The Genius On Elm St. Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Sticky-Fingers Cure Kristy and Kidnapper

Kristy and Kidnapper Baby-Sitters Club 041

Baby-Sitters Club 041 Karen's Bunny Trouble

Karen's Bunny Trouble Baby-Sitters Club 032

Baby-Sitters Club 032 Diary Three

Diary Three Christmas Chiller

Christmas Chiller Karen's Half-Birthday

Karen's Half-Birthday Needle and Thread

Needle and Thread Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier

Secret Life of Mary Anne Spier Baby-Sitters Beware

Baby-Sitters Beware Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out

Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out Logan Likes Mary Anne !

Logan Likes Mary Anne ! Baby-Sitters Club 061

Baby-Sitters Club 061 Best Friends

Best Friends Baby-Sitters Club 031

Baby-Sitters Club 031 Karen's Little Witch

Karen's Little Witch Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter

Jessi Ramsey, Petsitter Baby-Sitters Club 123

Baby-Sitters Club 123 Baby-Sitters Club 059

Baby-Sitters Club 059 Baby-Sitters Club 033

Baby-Sitters Club 033 Baby-Sitters Club 060

Baby-Sitters Club 060 Baby-Sitters Club 094

Baby-Sitters Club 094 The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart

The Baby-Sitters Club #99: Stacey's Broken Heart The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #109: Mary Anne to the Rescue (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Mystery At Claudia's House

Mystery At Claudia's House Claudia And The Sad Goodbye

Claudia And The Sad Goodbye Mary Anne's Big Break-Up

Mary Anne's Big Break-Up Baby-Sitters Club 025

Baby-Sitters Club 025 Baby-Sitters Club 042

Baby-Sitters Club 042 Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House

Stacey and the Mystery of the Empty House Karen's Baby-Sitter

Karen's Baby-Sitter Claudia's Friendship Feud

Claudia's Friendship Feud Baby-Sitters Club 090

Baby-Sitters Club 090 Baby-Sitters Club 021

Baby-Sitters Club 021 Baby-Sitters Club 056

Baby-Sitters Club 056 Baby-Sitters Club 040

Baby-Sitters Club 040 The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The)

The Baby-Sitters Club #108: Don't Give Up, Mallory (Baby-Sitters Club, The) Dawn and the Impossible Three

Dawn and the Impossible Three The Snow War

The Snow War Special Delivery

Special Delivery Baby-Sitters Club 057

Baby-Sitters Club 057 Mary Anne And Too Many Babies

Mary Anne And Too Many Babies Baby-Sitters Club 030

Baby-Sitters Club 030